They say if you remember the ’60s you probably weren’t there. That may be true for the San Francisco hippie crowd, but for hunters it was a time of transition and I remember it well.

When I was growing up my family had strict rules about kids and deer hunting. I thought I was ready by the time I entered first grade, but my father said I had to be 12. (He later caved in to my persistence and let me start when I was 11.) In 1965 I was 10 and considered too young to go deer hunting with the guys, so I spent opening morning in my room, mad as hell and impatiently waiting for the gang to show up for lunch. They were late and all excited about a buck one of them had jumped on the way out to the truck. That was back when Vermont was full of deer and even more full of deer hunters, and the buck had run past a bunch of out-of-state hunters gathered for lunch on the edge of a small meadow. That bunch emptied their guns at him, but the buck was retaining all his body fluids when last seen.

The guys were all talking about a cartridge case Dad found in the pile of empty brass. It was passed around the table, but nobody had ever heard of it. Until it finally got to me. I had ordered every gun or ammo catalog I could find. I poured over them until I could recite them by memory. I knew the cartridge.

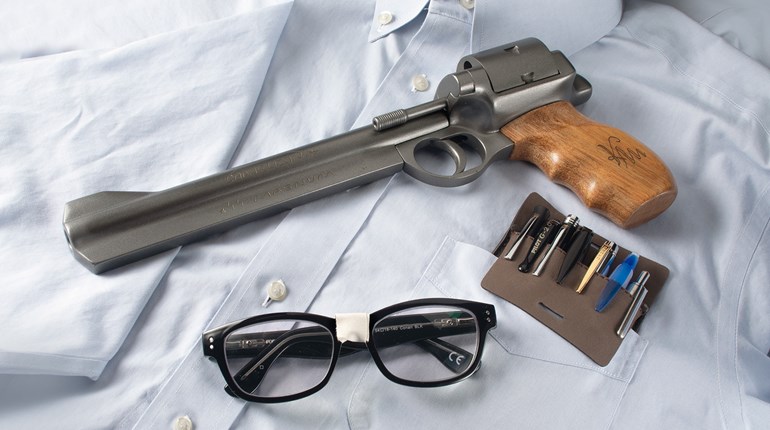

That guy might not have been much of a shot, but as far as I was concerned he was riding the ragged cutting edge of “cool” with his choice of deer rifles. He was shooting the .444 Marlin, at that time the most powerful lever action on the planet.

Introduced in 1964, the .444 Marlin pushed a 240-grain bullet to a muzzle velocity of 2350 fps. I couldn’t believe a guy cool enough to have a .444 Marlin would have missed that buck, and I insisted the men go back and look again for a blood trail. Or at least find some more brass for my collection.

My request was ignored, and when the men headed back to the woods after lunch, again without me, I vowed two things. First, when I got older and had children of my own I would never leave them behind if they wanted to go hunting with me. Secondly, I vowed I would one day have a .444 Marlin. I am happy to say I kept both promises.

The Strange Mix of the ’60s

It’s interesting to look at how rifles and cartridges for deer hunting have changed over the years, even in my lifetime. It’s often said the war to end all wars, World War I, was the catalyst for change. The doughboys coming home were enamored with their bolt-action rifles and high-speed, bottleneck cartridges. But it took a while for the message to filter down to my little part of New England.

I lived in a small town, and just around the corner from our house was the “Locker Plant,” which was our local meat processer. I was part of a gang of boys who hung out there every weekend to see the deer brought in for processing. Often there was a long line, and I would pick the brains of the waiting hunters about their guns. Later, when my father and uncle relented and let me go to deer camp on daytrips, I spent all my time checking out the rifles and asking too many questions. I lost track of the firewood I hauled and how many times I swept the floor as penance.

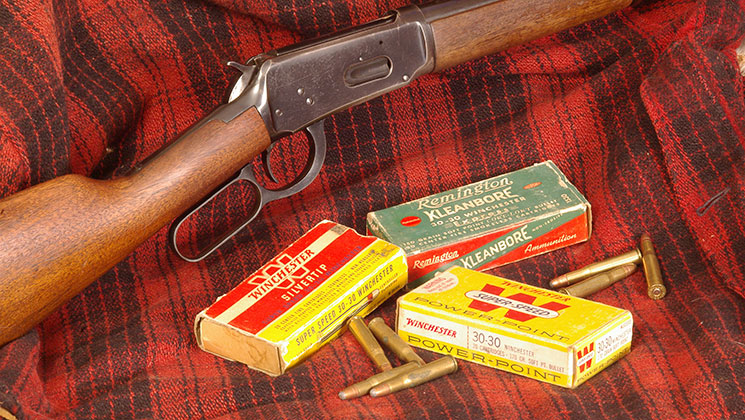

In the mid-’60s, lever-action rifles still ruled the roost. Without a doubt the Winchester Model 94 in .30-30 Winchester was king, but the .32 Special had a huge following, too. There was always a smattering of Marlin lever actions, usually in .30-30 but a few in .35 Remington. Speaking of the .35 Rem., it was not uncommon to see the odd looking Remington Model 8 or the newer Model 81, semi-auto rifles, almost always in .35 Rem., in the hands of a deep-woods hunter.

I shot my first whitetail in 1966 with a Winchester Model 1892 in .38-40. Gramp loaned me the gun, but I was on my own for ammo. Lindsey Baker’s general store broke up a box and sold me half a dozen cartridges for a dime each, as I recall. I used every single one of them on that deer.

The 1892 and even the 1876 in .38-40 and .44-40 were still seeing some use. The gun guys, those in the know back then, often carried a Savage Model 99 in .300 Savage or .250-3000 Savage. My grandfather was a hardcore gun guy and he used a Winchester 1886 in .45-70. Once in a great while a Winchester Model 71 in .348 Winchester showed up, but they were rare. One guy in our camp had a Model 88 Winchester lever action in .308 Win., which was pretty cutting edge. A few hunters were using the older Remington Model 141 pump-action rifles, usually in .30 Rem., which was a ballistic clone of the .30-30. A lot of the more hip and happening hunters had Remington 740 and 742 semi-auto rifles, almost always in .30-06.

A few hunters used bolt actions, but they were far from the majority as they are today. The first modern bolt action I saw in our camp was used by one of the younger guys. The 20-something hunter carried a big, heavy Savage in .270 Winchester, fitted with a huge variable-power scope. The older guys dismissed it as “uppity” and “fine for hunting out West, but no damn good here in the woods.” The guy who owned it brought in more bucks than just about anybody else in camp.

I was the next to exclusively use a modern bolt action in our camp when I bought a Remington Model 788 in .243 Winchester in 1968.

In the ’60s you could buy military surplus rifles just about any place. I can remember a big wooden barrel full of them in King’s department store. They were cheap and I lived in an economically depressed area, so a lot of those guns—old Mausers in a number of cartridges and some Krags in .30-40—made it into the woods. I had a Krag in a carbine, which I later foolishly traded. There were a few Springfields in .30-06. One of my buddies used his grandfather’s 7.65 Argentine Mauser. Surplus Japanese Arisaka rifles in 7.7x58mm or 6.5x50mm Japanese were pretty common. One we saw pretty often was the 6.5 Carcano, because you could find one cheap, often with a scope mounted. But after the Gun Control Act of 1968 passed the cheap military surplus guns just about dried up in the hunting woods.

In the ’60s you could buy military surplus rifles just about any place. I can remember a big wooden barrel full of them in King’s department store. They were cheap and I lived in an economically depressed area, so a lot of those guns—old Mausers in a number of cartridges and some Krags in .30-40—made it into the woods. I had a Krag in a carbine, which I later foolishly traded. There were a few Springfields in .30-06. One of my buddies used his grandfather’s 7.65 Argentine Mauser. Surplus Japanese Arisaka rifles in 7.7x58mm or 6.5x50mm Japanese were pretty common. One we saw pretty often was the 6.5 Carcano, because you could find one cheap, often with a scope mounted. But after the Gun Control Act of 1968 passed the cheap military surplus guns just about dried up in the hunting woods.

Some military guns stuck around as “sporterized” rifles, usually looking like they were hacked on by a back-shed gunsmith with a dull chain saw and a horseshoe file. The hardcore guys harvested the actions and used them for custom rifle builds, almost without fail in .30-06 or .270 Win.

My uncle had a really bad experience with a black bear while he was using a .38-55 lever-action Marlin. In spite of multiple hits, he killed the charging boar with the last cartridge in his gun at powder-burn distance. He showed up the next year with a Remington 760 pump in .270 Win. That was the first 760 most of us ever saw, but certainly not the last.

The Bolt-Action Surge

The cover of the September 1970 issue of Sports Afield was a photo of Larry Benoit staring down a Remington Model 742. The text revealed that he actually hunted with a 760 Carbine, and that launched a revolution in the Northeast deer woods. Within a few years half the hunters there carried a Remington pump action in ʼ06 or .270.

The whitetail hunting boom was on; the whitetail was becoming the dominant big game of North America. Several magazines launched that focused exclusively on hunting whitetails, and gunmakers took note.

As we transitioned into the ’80s, Winchester tried to bring back the lever action with its Big Bore, introduced in 1978 in .375 Winchester. In 1980 it added the .307 and .356 Winchester. It was an attempt to reclaim faded glory, but the public had moved on. It’s a shame, though. I have one in .356 that served me well for several years of deer hunting.

The pump action remained king in the Northeast, but as the ’80s approached we witnessed a surge in bolt-action rifles. It was driven by better accuracy, the powerful, flat-shooting cartridges and better triggers; and for Eastern hunters by the smaller, lighter rifles appearing on dealer shelves, like the Remington Model 7, introduced in 1983. It was a perfect mate with the 7mm-08 Remington, introduced in 1980.

Lighter-weight bolt actions continued to make inroads through the ’80s. Guns like the Remington Model 700 Mountain Rifle, Winchester Model 70 XTR Featherweight and Browning Micro-Medallion attracted the next generation of Eastern whitetail hunters. For a while the Mountain Rifle in .280 Remington was the company’s best seller.

By the mid- to late-’80s, synthetic stocks on bolt actions were becoming popular, as were stainless steel rifles. This solved one of the lingering problems for hunters in the often wet Northeast, and helped to drive more hunters to bolt actions.

A Magnum Boom

The magnum boom started in the late ’50s and early ’60s, but it never really caught on in the Northeast. Early innovators who used the cartridges reported massive meat damage from close-range impacts. Of course that problem was caused by poor bullets available at the time, but it damaged the reputation of the cartridges.

Better bullets and more awareness helped some hunters see the ballistic advantage of these cartridges. And by the early ’90s whitetail hunters were looking at long-range options. Even in the heavily wooded Northeast a lot of hunters became interested in shooting down a powerline or across a clear-cut. Gunmakers responded with rifles designed for long range like the Remington Model 700 Sendero and the Winchester Model 70 Laredo. These were in effect heavy-barrel varmint-style rifles, but often chambered for magnum cartridges like the 7mm Remington Magnum or .300 Winchester Magnum. This all helped focus more attention on magnum cartridges, and combined with a wave of new, highly engineered bullets designed to work with these cartridges, long-range hunters flocked to them.

Weatherby brought this long-range fad to a crescendo in 1996 with the introduction of its .30-378 Weatherby. I was at the writer’s seminar where it was introduced. One of the Weatherby executives told me the company expected to sell a few to elk hunters, but otherwise, sales projections were not high. I said he was wrong; whitetail guys would buy all they could make. He later admitted I was right, and that they could not keep up with demand.

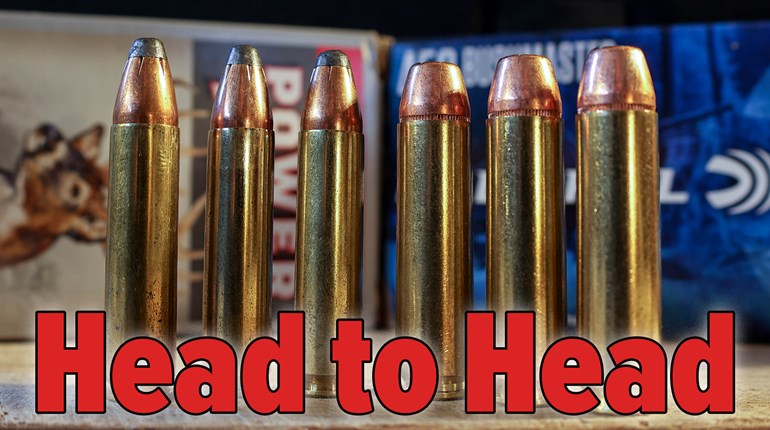

Until then, “magnum” almost always meant the case was designed around the old H&H belted magnum design. Remington changed the game in 1999 with its introduction of the belt-free Ultra Mag line. That started a movement toward beltless magnum cartridges. Winchester followed at the turn of the century with its line of beltless short magnums. Hunters who were intimidated by the recoil and blast of RUMs then had an alternative, and the short magnums took off. Remington added its own line of short magnums in 2001. Ruger jumped in with Ruger Compact Magnums in 2008. For a while, the short magnums were some of the most popular cartridges in the deer woods.

I was in the room with several other writers when Winchester proposed its super-short magnums and asked our advice. The company didn’t listen and introduced them in 2002 anyway. Winchester was trying to ride a good thing too far; the WSSM cartridges died a merciful death when Winchester closed its New Haven plant in 2006. And as the first decade of the new millennium decayed, short magnums began to lose a bit of their luster.

ARs Come Home

During a time of wars in the Middle East, a lot of attention has turned to the AR rifle platform that so many returning vets have used in the military. It’s common for military rifles and cartridges to become popular with hunters, but the AR-15 had been the exception. It was introduced in the Vietnam era, but vets coming home then didn’t want anything to do with it. The generation of warriors returning from Iraq and Afghanistan do.

The AR-15 and larger AR-10 (ARL) rifles have become hugely popular, not just for target shooters but with hunters as well. The guns long had a following with predator hunters, but now deer hunters use them. The smaller AR-15 was designed around the .223 Remington. While that cartridge sees some use for deer hunting, it’s hard to argue that it’s adequate. The emergence of big-bore cartridges like the .50 Beowulf, .458 SOCOM and .450 Bushmaster turned the rifle into a viable whitetail hunting machine. The .30 Remington AR cartridge was introduced in 2008, and it duplicated the ballistics of the .300 Savage, one of the most successful whitetail cartridges of all time. Other cartridges such as the 6.8 SPC and 6.5 Grendel also make the AR-15 a viable deer gun.

The ARL platform was built around the .308 Win., so it adapted well to that family of cartridges. While the .308 is by far the most popular, I am fond of the .338 Federal in an ARL for hunting deer.

The 6.5 Creedmoor was initially introduced in a DPMS ARL; it’s currently one of the most popular cartridges on Earth. The cartridge was developed for long-range target shooting, but has also found favor with hunters. While I cringe at some of the claims about its performance (slaying large dragons at seven leagues and the like), the truth is it’s a great deer cartridge when used at ethical hunting ranges. It’s not magic, as one Internet fan-boy suggested, but it is competent.

Where the 6.5 Creedmoor has really solidified a base, though, is with the long-range shooters using precision rifles. A precision rifle is a purpose-driven bolt action designed for use in long-range target shooting. Those shooters, particularly the competition shooters, have moved away from magnum cartridges and into more sedate cartridges with moderate velocity and very high ballistic coefficient bullets. Some of them are using their precision rifles to shoot deer.

The success of the 6.5 Creedmoor spawned a huge resurgence in interest in the 6.5mm bullet diameter. It’s been around since the 1890s in European cartridges, but Americans never really took to 6.5’s. The .264 Winchester Magnum petered out rather quickly, and the 6.5 Remington Magnum never really got started. The .260 Remington tried to hide its 6.5 roots, as if it were ashamed. Then the 6.5 Creedmoor showed up and changed our thinking.

There has been a lot of interest in more powerful, arguably better 6.5 cartridges for hunting at long range. The 6.5-284, 6.5 Nosler, 6.5-300 Weatherby Magnum and 6.5 PRC have all pushed the 6.5 bullet a little faster. This, too, has driven development of other long-range cartridges in more conventional bullet diameters, like the .28 and .30 Nosler.

Gunmakers are responding with hybrid rifles that meld the best features of precision rifles and hunting rifles. This new generation of long-range hunting rifle has become popular with a lot of deer hunters wanting to stretch the distance.

Rifles, optics, cartridges and bullets have advanced as has our knowledge of shooting over distance, and long-range deer hunting is the hottest thing going on today.

Considering the Model 94 lever action in .30-30 was the gun du jour when I started hunting whitetails, it has been a long, strange trip indeed.