It was a long time ago and memories usually fade, but not this one. It’s funny how that works; some just stay with you.

I was just getting started as a writer and still feeling my way along the confusing and intimidating pathway. I wasn’t there because I had proven much of anything on paper, I was just lucky enough to have my name drawn from the jar. I was obsessed with hunting black bears so when I won a Maine bear hunt in the New England Outdoor Writers Association’s raffle, life was good.

Except that I was so focused on the hunting I ignored that sometimes the important parts of a hunt aren’t measured at the game pole.

We were in a tiny cabin on the shore of a lake in eastern Maine, four big guys tightly packed into a space that would be crowded with a single adult. The outfitter was friends with the legendary Alabama turkey hunter Ben Rogers Lee and had invited him to join us. But Ben could never fit in the cabin so he stayed in town instead. Each day when he arrived at the “Hovel,” it was like the planet shifted up a gear.

We have all heard the term about people who suck the oxygen out of a room. Ben sucked it out of the world. I don’t know what other cliché describes him because “bigger than life” is not enough. Ben dominated every situation and nobody really minded. He was fun and funny, and I don’t think I have ever laughed so much in my life as I did on that bear hunt. Ben became a good friend, but when that many alpha males gather together and you are a guest who needs to behave, sometimes you just need a break.

I had wandered away looking for some solitude and I spotted a guy sitting off by himself, writing in a notebook. He had come with Ben and we had all been introduced, but I had forgotten his name already. Clearly he needed a break, too, and I didn’t want to intrude, but at his invitation I sat down and said hello.

Tony Kinton was a well-known Southern outdoor writer and had come as Ben’s guest on the hunt. It’s hard for a quiet guy to get noticed when Ben is holding court, but Tony wasn’t the kind who cared. We started talking and launched a friendship that has endured for more than 30 years.

I traveled to his home in Mississippi to hunt deer that fall and the next year we damn near froze to death in a tent in Montana’s Missouri River Breaks. We hunted bears in New Brunswick, caribou in Quebec and were on our way to a moose hunt in British Columbia when word reached us at the airport of Ben Lee’s death. From bumping the butt of a moose down the road at 30 mph with the hood of my van and exploring spooky lost valleys in forgotten wild country to trapping 50 mice in a single night in a remote trailer in Montana, we had a lot of adventures together.

■■■

Then life kind of happened. Tony took a new job teaching at a local college. I started a family and a business and finally found some success with writing. We both got too busy to go hunting together, and without notice the years just passed.

We hooked up to share a room at the SHOT Show now and then and perhaps exchanged an email or two, all while somebody turned up the speed of life and it moved too damn fast. One day you wake up and realize decades of your life have passed, and somehow your focus has become clouded and distorted. I don’t have all that many true friends, and I understand that ignoring them will only lead to regrets at the end.

I called Tony and said, “Let’s go hunting.”

And then it began. We all know the dance of the Modern American.

“I can’t find the time.”

“My schedule is too busy.”

“I have obligations.”

“There isn’t enough money right now.”

“I have things to do, maybe next year.”

“I can’t.”

It’s all so damn predictable and tragic. Nobody ever lay in their deathbed and complained they didn’t mow the lawn enough.

Actually, that’s not fair. This was a two-way problem and we both had serious obligations, family members who depended on us, but the point is valid: Life is fluid and dynamic. The obligations are always there in one form or another. If you let them control everything it all just passes by and you never make that hunting trip. You just have to find a way.

Last year, after weeks of discussions about exotic adventures in wild places chasing mysterious critters and hunts that neither one of us could ever seem to make work, I hit on an idea. “Let’s hunt in Mississippi again. It’s been 30 years, maybe it’s time. Besides, I can use a break from the brutal winters here in Vermont.”

So that’s how we ended up in a rustic camp on the edge of the Mississippi-Yazoo Delta country with frozen fingers, frozen water pipes and having the time of our lives. The cold followed me south. I am not sure if the temperature set an official record for the coldest ever in Mississippi, but if it didn’t it was only because the thermometer froze.

■■■

If nothing else, the years have mellowed me just a little and I adjusted to the slower Southern pace better than I did in the ’80s. In the past, I would have been champing at the bit to get going the first morning, but we had other plans that suited the new me just fine. The deer would still be there.

That first morning we had a leisurely breakfast at Tony’s house where I reconnected with some of the old friends I had met on the early trips. Harold Wiggins and H.L. Goolsby are Tony’s buddies and shared some of our adventures. In fact, Goolsby saved my life in the Arctic back in the late ’80s after I fell into a sinkhole with a 200-pound pack of caribou meat on my back. I let my youthful impatience get the better of me and had gone on ahead of the rest of the party. I thought I was alone when, in the gathering twilight, I didn’t see the hidden, boggy hole and stumbled in face-first. I had my rifle above my head, across the inverted antlers sticking out of the top of the bag, and my hands were wound up in the sling to hold it. With that heavy bag on my back and my hands trapped, I was drowning and I doubt I would have made it until the other guys showed up. I had no idea H.L. was just as impatient and was right behind me, but if he had not pulled me out of that cold water, we probably would not have been enjoying Susan Kinton’s Southern cooking together on a fine January morning nearly 30 years later.

Tony had made arrangements for us to hunt with one of his old students who had remained a friend. Pat Martin had a small lease with some other friends and family not too far from Yazoo City, and he generously agreed to host our hunt.

The original plan was to stay in an old camper on the property, but with the cold temps and a heater that wasn’t going to work, Pat called in a favor with a buddy and found a camp a few miles away. It was a nice place: clean, cozy, rustic, perfect for a deer hunt. Except that the water pipes had frozen in the brutal cold. The first few days, rather than cook, we ate catfish or burgers at a local family-owned restaurant that didn’t seem to mind none of us had showered and our clothes were a little bloody.

The last night there, we washed up with bottled water and grilled whitetail backstrap along with some kind of fish from the Gulf Coast whose name baffles this misplaced Yankee. We ate until we bulged, all the while loudly swapping hunting stories. It was everything a final evening in a hunting camp should be.

■■■

I have hunted Mississippi a bunch of times since that first hunt with Tony so many years ago. I have taken some very good bucks there and I knew from experience the Magnolia State can produce some very nice whitetails. We were in a great place with the potential for good deer and it made sense to be patient. So I wasn’t in too much of a hurry to pull the trigger.

I have hunted Mississippi a bunch of times since that first hunt with Tony so many years ago. I have taken some very good bucks there and I knew from experience the Magnolia State can produce some very nice whitetails. We were in a great place with the potential for good deer and it made sense to be patient. So I wasn’t in too much of a hurry to pull the trigger.

At least that’s what I kept telling myself. Mellowed out or not, I am a hunter. I live to hunt, and if the day ever comes when I can sit in a deer stand without some anxiety and stress it’s probably the day I should hang up my guns.

The cold had the deer off their schedules, and the hunting was turning out to be tougher than expected. Pat had photos of a lot of big bucks on his trail cameras. We had also seen one bruiser on the edge of a field when we first arrived. There were rubs and scrapes all over the place and no doubt there were some very good bucks lurking about, but the indications were they had either frozen to death or were piled up like hogs under a cedar tree trying to keep warm. Either way, the action was a little slow at the deer stands.

Of course, I need to put that in perspective. I had just spent 15 days hunting in Vermont just to find one legal deer to shoot, and that was a doe. A lot of those days I didn’t even see a deer. Two bad winters in a row had been rough on our mismanaged deer herd. So when, even on a “slow” hunt in Mississippi, I was seeing deer it was a huge improvement. Each time in the stand I saw does, fawns and a few little bucks. That’s an improvement by any standard.

I love trophy deer, but I love backstaps even more. There is a point when the light fades enough that you can’t judge a buck without risking a mistake. I know this from hard experience. I once hunted a place in Alabama with a strict rule about antler size. I watched a buck in the fading light I had no doubt would more than pass inspection, but I wound up writing a $500 check for lack of an inch. There were no such rules here with Pat, but I didn’t want to abuse the hospitality by shooting the wrong buck and skewing their management efforts.

So I watched for that point when the light crossed over into “screw-up” country. Then it was doe-shooting time. For 20 minutes, I had kept my eye on a big doe as she fed in the green-field in front of me. When it was time, I picked up my custom .280 Ackley Improved and drew the first blood on the hunt.

I built this rifle with help from custom gunmaker Mark Bansner. It’s fitted with a Swarovski scope and may be the epitome of the perfect rifle for hunting Southern green-fields. It’s flat-shooting, extremely accurate and the scope is so bright you would swear it has its own light source.

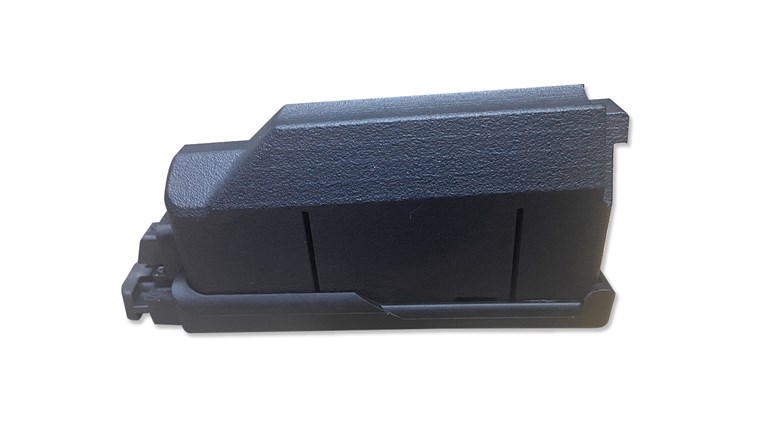

Tony, on the other hand, is of the opinion that any gun made after the turn of the century (and not the most recent one) is too new to use. If he must use a firearm, he prefers a flintlock. At my prodding he agreed to go modern on this hunt and brought a single-shot Sharps rifle loaded with black powder and a cast bullet. It had a long, old-timey-looking scope on it that appeared to have been made in the days when machines were turned with overhead buffalo-hide belts, the glass was hand blown on an open forge and the crosshairs were made from spiderwebs. He apologized for cheating by using an optic.

Anyway, the next day he “made smoke” and also added a doe to the larder. Bucks, however, were still proving hard to find.

■■■

The best hunts are always emotional rollercoasters. You can’t appreciate the highs without the lows. By day three the lows, at least in terms of deer shot, were way ahead on the scorecard.

One of Pat’s buddies, David Welch, shot at a big buck just before dark the second night. The next morning we looked for a long time before somebody found a blood trail. Because we are all expert woodsmen, we were able to track the spotty and sparse drops for several hundred yards down a remote path through the woods.

Any hunter knows the drill. We would look and look and just about the time we were going to give up, somebody would find a speck of blood. Then we would rinse and repeat. We continued this way for some time and even remarked that the buck must have been hit hard because he was sticking to the path where the walking was easier than in the thick brush beside it.

Finally somebody mentioned that they had brought Tony’s deer out on this trail the day before. It turned out that the drops of blood we were finding were drips that ran off the bed of the 4x4 and dribbled to the ground.

Tracking a 4x4 is usually easy, but blood-trailing one takes a special kind of skill set. I felt like a fool then, and feel more like one telling this story, but it’s too good not to tell. Besides, I have a reason.

The upside of the story is we tracked that wounded 4x4 past another deer stand that just reached out and grabbed me. Sometimes that happens. I see a stand and I just know I’ll shoot a deer there. It could be that my woods skills are so finely honed that I recognize the travel patterns and habitat of a buck instantly. Or it might be that I have inherited a bit of psychic skill from my grandmother. Or, most likely, that’s all just hooey and the stand looks comfortable.

No matter, that’s where I was the next, last morning: sitting in the frost and wishing I had brought warmer boots. Sometime before the sun climbed above the trees, I caught a flicker of movement off to my right. I watched for a very long time until it turned into a buck.

He appeared to be a healthy 2-year-old: tempting, particularly this late in the hunt, but not quite big enough. I thought hard and started for my rifle a few times, but in the end I decided to pass. Then I second-guessed myself over and over as I watched him slowly make his way through the brush and off to parts unknown. Probably to join that hog pile of deer so he could warm up his hooves a bit. I was happy to see him and glad when he was gone. The decision not to shoot him was final then. I could relax.

I spent the next half-hour watching the patterns my breath made when I exhaled into the cold air and trying not to shiver, until another flash of movement in about the same place caught my eye. I slowly turned and this time I could see a good set of antlers slipping through the thick brush. The trouble was, I couldn’t see a deer, just the antlers.

Applying a bit of logic, I figured there had to be a buck under there someplace, so I slowly turned and got my rifle ready. Then a bit of deer showed through the brush, followed by just a little bit more and a little more after that. I found a little tunnel through the brush and when a small patch of his neck and shoulder showed at the end, I sent a bullet on through to say hello.

I waited to make sure, but he was finished. I climbed down and walked over to spend a little time with the deer. I sat there with him, enjoying the quiet morning and thinking that sometimes the best hunting adventures are the simplest and the least expected.