We couldn’t see the ducks through the canopy of trees, but that didn’t stop Lamar Boyd from laying on the highballs thicker than the sawmill gravy we’d devoured at breakfast. I wouldn’t have even known they were overhead at all, had they not soon thereafter floated down through a small window in the oaks and landed amid our decoys with hardly more than a feathery splish, just like they’d done for generations.

Where I reside in the Prairie Pothole Region, a contest-caliber highball call unleashed blindly at bare sky would make your buddies look at you like you’d lost your marbles, because nobody calls until they can actually see ducks to work them. Then again, we don’t have centuries-old cypress trees and adapted water oaks that form a near-impenetrable leaf-and-lumber umbrella over our stock tanks, either. So I’m thankful for the rare times I get to hunt ducks in true Southern style amid historic haunts because it renews my appreciation for the art of calling ducks. I’m also thankful for the few places in the world that time seemingly forgets, and for an even rarer glimpse back into history, when few things were more enjoyable as watching greenheads cup up and filter through flooded timber, where every sight is dramatized over such a backdrop, every sound magnified like echoes in nature’s amphitheater.

If you’re from Maryland you might think waterfowling was born amid its gray-waved Chesapeake Bay flats, and you’d likely be right from a purely chronological perspective. Likely when you think of romantic times on the water you envision sinkboats, long lines of bluebill blocks, crabby watermen, salt swells, old squaws low in the fog and bushels of oysters after the hunt. Even if some of these things were before your day, you no doubt remember your father’s and grandfather’s stories as vividly as if they were your own.

But probably half the country sees it a skosh differently, largely thanks at least in part to influential Southern writers like Golden-era Tennessee outdoorsman and author Nash Buckingham (1880-1971). He didn’t define duck hunting in the Southern style, but merely poeticized it by describing it in color.

You see, the South has a unique way of borrowing recipes, adding its own regional flavors and excess butter to the roux then franchising the now-decadent dish until it’s rebranded as its own. (Southerners might disagree that they borrowed anything except maybe some French-Creole spice, and they might be right, but it doesn’t matter really.) The South’s proud patrons have a knack at taking otherwise fairly strenuous outdoor activities such as hunting, tailgating or camping, and making them as enjoyable as possible via creativity, planning and innovation in order to extract maximum pleasure from them. Take duck hunting, for example. What was for generations up North a hunker-in-the-brush-and-mud-until-you-kill-a-few-ducks-or-get-too-cold-to-stand-it-anymore-endeavor evolved in the South, namely Mississippi, into a gentlemanly exercise of taming the elements so the hunt is made to be as effortless as eating crumpets on the king’s lawn for as long as he’ll put up with you, regardless of the weather.

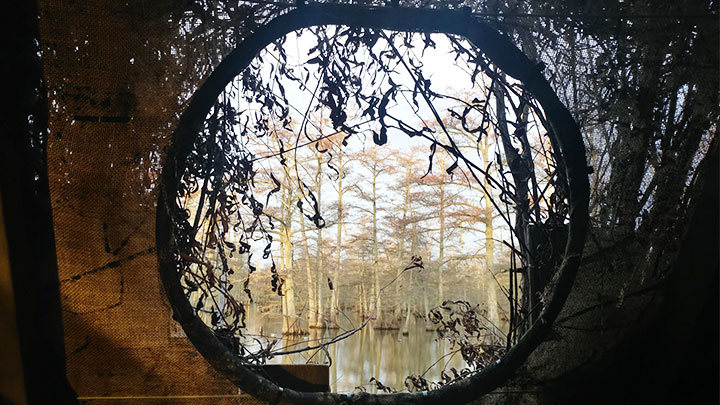

Rather than hastily stringing up a shard or two of canvas as a makeshift blind in the moments before dawn, turn-of-the-century Southern waterfowlers constructed permanent, over-the-water blinds on their favorite waterholes. In the downtimes between flights of greenheads when a man can really think about his situation and how to improve upon it, these “blinds” became full-fledged cabins, what with covered boat docks, hinged doors, outhouses, shooting ports/windows, dugout-style bench seating, shingled roofs, planked floors, tar paper-lined walls and chimneys for stoves that reignited duck hunters’ enthusiasm as well as the bacon and coffee. While some call it Southern ingenuity, others shake their heads at the sheer excess of it all. Most Mississippians just call it natural progression.

Once the money and work were invested on these duck-hunting vacation homes built over traditional landing zones, it was no mystery—except perhaps to them at the time—why wives back in Memphis or Ft. Smith or Jackson began seeing their men much less during the hunting season.

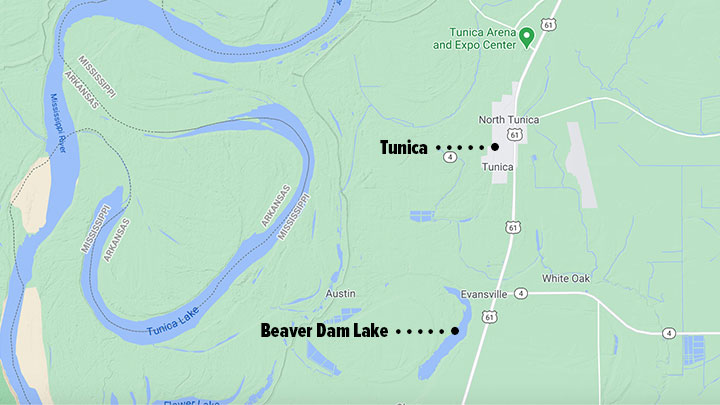

Such setups made duck hunting—procuring wild fowl for the dinner table—an all-day, all-weekend, near-all-season affair now that hunters weren’t forced to retreat at lunchtime for fuel and defrosting. As word spread, more men wanted in—yet they also knew they had to work together to make sure their coveted holes weren’t shot out by everybody going out all at once—and so duck hunting clubs were established up and down the heart of the Mississippi Flyway. One of the more famous areas was located near the cotton-pickin’ town of Tunica. One of the more famous holes sat between the Mississippi and Coldwater Rivers, just south of Tunica and east of Evansville, in the middle of a water-filled woods called Beaver Dam Lake.

We know about these rather secret fraternities of double-barrel toting, duck-cotton coat wearing, pioneers of waterfowling luxury—and about this hole specifically—due to the likes of “Big Mouth” (that’s my nickname for him) Buckingham who broke man code when he waxed so poetically about the happy times he spent hunting there. It seems the whole hunting world went buck-wild over his books, and cherish the nostalgia of them today.

To be frank, my mother gave me several Buckingham books while I was a mere greenwing, and although I read them, they weren’t my favorites, as I had moved to Oklahoma from a Memphis I was too young to remember, and subsequently I discovered other styles of hunting in the very unromantic and un-Southernly potholes and government watersheds there. (We called our style “pond hopping,” and you most certainly can’t eat grits and drink coffee while engaged in it.)

I do recall vividly, however, my late father talking about hunting ducks amid the marshes, brackish bayous and flooded timber of the mighty river for which his native state is named. He spent much time in Tunica long before the casinos brought it newfound wealth, when the place was just a low-rent housing district amid sharecropping farms. Its lake, a huge oxbow of the river called Tunica Cutoff, was a weekend oasis and mosquito breeding ground where he and my mother would fish for bluegill and crappie, water ski and generally have a great time before my burden came about. In the winter he too preferred a Fox shotgun for wingshooting, much like dear Buckingham, who so absentmindedly left his on the back of a hunting buddy’s car in 1948—just as I likely would do today if I had something so nice.

The legendary Super Fox double-barrel 12-gauge—nicknamed “Bo Whoop” for the reported sound it made when Buckingham fired from the timber—didn’t resurface until 2005; it was auctioned in 2010 for a measly $201,250, but then was donated by the winning Howard family to Ducks Unlimited. It was subsequently taken to Beaver Dam Lake a few years ago by a group of outdoor writers who shot ducks with it. Surprisingly, it didn’t disappear again … which pulls me from my digression on Buckingham and my father, and back into reality and the notion that while times have changed, if you’re looking for a throwback to simpler times past, a live-aboard blind hidden deep in a dark cypress maze somewhere on Beaver Dam Lake will do it, just as it has for generations of waterfowlers before me who haven’t always only hunted just for food.

“Take ’em,” grumbled Lamar or his father, Mike, down the line—or maybe it was old Buck himself—and the six of us made the decoy-facing side of the blind tremor and belch fire like Old Ironsides by the way we shoved our barrels uniformly from the shooting ports and opened up in a volley of shot that shattered the serenity of our canopied sanctuary. Greenheads balled up and cratered the smooth carpet of algae-water like divots on the 5th green at Augusta. I’m pretty sure I downed the fattest drake mallard of that bunch, but as all Southern duck hunters are taught, claiming one when you’re a mere barrel in the battery can only be done in a joking fashion or else you might soon find yourself spending more time at home with your loved ones during hunting season.

Lamar is a third-generation duck hunter/guide on Beaver Dam, and let’s just say he hit the duck-hunting lotto when he grew up in these parts. Beaver Dam Lake is a 1,500-acre, shallow water impoundment that when photographed from any location from any angle, in any light, looks like it could be the cover of South Carolina Wildlife each and every month. It provides home and habitat for countless animal species, from amphibians and reptiles, birds, mammals, fish, insects and at times in the fall, a keen-eyed Labrador or two. The lake is now privately owned, and the Boyds’ near-40-year-old guiding operation—fittingly called Beaver Dam Hunting Services—is the lake’s only official way on.

Years ago Lamar’s grandfather bought a goodly plot of lakefront land, and, as they say, is now grandfathered in. All three of the Boyd boys have subsequently built houses on Beaver Dam’s shore, where all they must do to hunt ducks each morning on perhaps the most famous piece of waterfowling water on the planet is to pry themselves from their beds and biscuits before traipsing several long yards down a path to a waiting jon boat (while wearing cumbersome waders, no less!).

When the Boyds aren’t guiding clients for mallards, widgeons, gadwalls, pintails, blackjacks, teal and woodies, they’re farming the fertile Delta land for rice and grain. But I got the distinct impression—judging by the smoothness of their duck calls and by the secret-knowing gleam in their eyes when they’re looking up through those bearded oaks—that these boys live not for Julys on the John Deere, but rather for Decembers blind-deep in ducks.

As for me, when I hunted in Mr. Buckingham’s historic hole, I immediately discovered why he was so very fond of it, and I, too, did not wish to leave. Had it not been for running out of shells—or me having a job back home or the fact that I was only paid through two days of hunting—I probably wouldn’t have. And now here I am, ole big-mouth Johnston, writing about my experience in the nostalgic flooded timber, because secrets so good and so rare are impossible to keep—nor should they be, I suppose.

Visit Mississippi

Besides duck hunting, the 20th-oldest state in the Union, Mississippi, is a sportsman’s haven. Its inshore and offshore fishing are wonderful from Pascagoula to Pearlington, with flounder, speckled trout, cobia, jack and snapper being the big draws. Between hunting or fishing trips you can bank on finding wonderful, purely Southern culinary experiences. Famous diners, such as the Blue and White Restaurant in Tunica, seafood restaurants, Cajun houses and BBQ joints dot the highways and townships if you’re up for a road trip. I once hunted Mississippi’s famous Giles Island near historic Natchez for trophy whitetails, and although I didn’t bag a giant whitetail, I sure ate a bunch. If you’re into music, check out Elvis’ birthplace in Tupelo, or, if you’re lucky, head to modern Tunica—or Biloxi—to stay at one of its many casinos. For more information, go to visitmississippi.org.

Hunt Beaver Dam

To arrange your hunt on historic Beaver Dam Lake, give Lamar or Mike Boyd a call or visit their website. It costs between $400-$500 per hunter, per day, depending on your lodging option. Fly into Memphis then drive to Tunica, or drive directly to the Boyds’ lodge near the water. 662-363-6288; beaverdamducks.com.