If you’ve hunted in Africa, it would be natural to wonder if you might have stalked the same “Green Hills” that Ernest Hemingway described in his “psuedo fictional” work, Green Hills of Africa. The book, divided into four parts (Pursuit and Conversation, Pursuit Remembered, Pursuit and Failure, and Pursuit as Happiness) chronicles a three-month-long safari in Tanganyika (now called Tanzania), East Africa. So, if you hunted anywhere else other than Tanzania, you can be sure you did not follow Papa’s footsteps in Africa.

As if writing a fictional novel, Hemingway wrote of his safari experiences in a unique narrative style that leans heavily on dialogue. Hemingway changed the names of his safari companions, including that of his “white hunter”—who happened to be none other than Philip Percival, the most famous and respected white hunter of his time, a man who had been a part of the Roosevelt safari. In later years, Percival mentored a whole generation of professional hunters, including Sid Downey and Harry Selby, and was acknowledged by his peers as the dean of professional hunters. He was elected to 34 consecutive terms as president of the East African Professional Hunters Association. Mentioned only in the dedication at the front of the book (“To Philip, to Charles and to Sully”), Percival’s character is called Jackson Phillips in the story and is often referred to as “Pop.”

I’ve read and reread the book several times over the years and each time, influenced by my own experiences in Africa, it proved to be a different story for me. If you read it before going to Africa, the impressions Hemingway presents of the continent, natives, game, countryside and safari dynamics will be quite different from what the book offers after you’ve been on safari—especially a hunting safari. But even for old safari hands, navigating the storyline’s dialogue is not always easy. Hemingway, either intentionally or unintentionally, hopscotches from one thought, conversation or event to another, offering a meandering stream of consciousness to follow.

■ ■ ■

Hemingway’s tale begins near the end of his safari as he and three native trackers sit in a blind watching a salt-lick “somewhere” in the middle of the Tanganyika bush. Pop, his white hunter, is conspicuous by his absence. It’s late in the afternoon and Hemingway and his native companions wait in silence for a greater kudu to show up. Their mood changes when they hear the noise of an approaching vehicle that becomes louder and more obtrusive as it labors up the main dirt road, passing a few hundred yards from the hidden group. The vehicle’s “clank of loud irregular explosions” spoils the hunt.

Irritated and frustrated by the vehicle’s interference, Hemingway laments that his time is running out owing to the imminent arrival of impending seasonal rains. The absolute last date for leaving the area is Feb. 17, which gives him only three more days to hunt. Once the rains break, the dirt roads will quickly become muddy quagmires that become impassable. More than a couple of days of rain will literally strand them where they are until the roads dry out, which could take weeks.

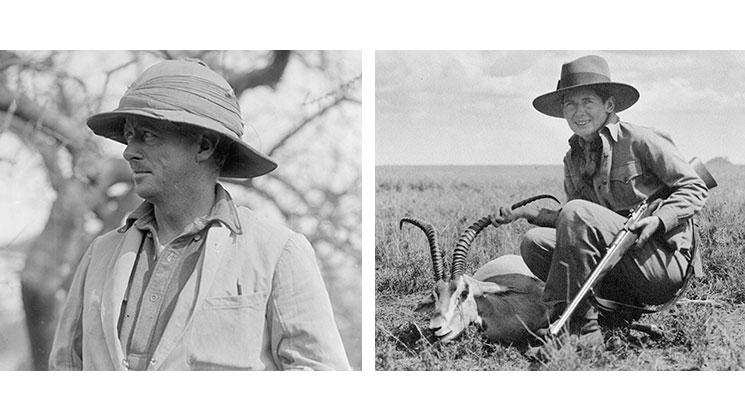

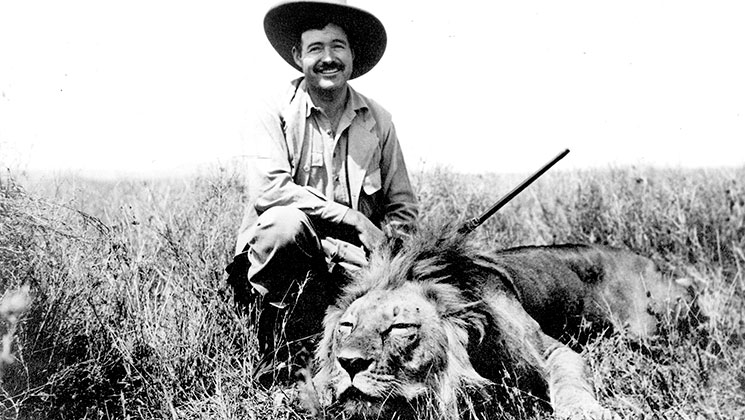

Hemingway’s safari began in December 1933 and continued to late February 1934, with the hunting taking place entirely in Tanganyika. Hemingway was accompanied by his second wife, Pauline Pfeiffer, whose uncle Gus bankrolled the three-month-long, $25,000 safari as the couple’s wedding gift. Also with Hemingway was Charles Thompson, his good friend from Key West, Fla., and who is referred to as “Karl” in the story. The Hemingway party traveled to Africa by ship, departing Marseilles on a steamer on Nov. 22, 1933, and arriving at Kenya’s port town of Mombasa sometime at the beginning of December. From Mombasa, they traveled on to Nairobi by train.

Percival might have met the arriving Hemingways and Thompson portside in Mombasa, or possibly at the train station in Nairobi. Among several white hunters introduced to Hemingway while he was in Nairobi was Bror Blixen, the ex-husband of Danish writer Karen Blixen (Isak Dinesen) and one of Pecival’s early partners in the safari business.

According to Pauline’s diary, they spent a couple of weeks in Nairobi provisioning the safari before departing for Tanganyika around Dec. 19. The camp equipment, provisions and safari crew were all transported on the back of two large trucks called “lorries.” Following along behind the lorries, or sometimes ahead of them, were the two hunting cars driven by Percival and Ben Fourie, the safari mechanic and stand-in for a second white hunter. Traveling in the hunting cars with their personal kit and guns were the Hemingways, Thompson and the gunbearers.

The Hemingway safari crossed from Kenya into Tanganyika at Namanga and continued on to the town of Arusha where game licenses and other documentation would have been issued. Upon departing Arusha, the safari vehicles pushed westward to the village of Mto wa Umbu, near where their first camp was pitched. From there, it was on to the Serengeti Plains near the shores of Lake Eyasi where a second tented camp was pitched. According to Pauline’s diary, that is where they celebrated Christmas Day 1933.

From the start, according to Pauline’s diary, Hemingway and Thompson’s shooting was atrocious, but bearing in mind they were shooting rifles with iron or aperture sights in very open country where game was seldom less than 200 yards away. Thompson outshot Hemingway—not that he was trying to outshine his friend; reportedly he simply had better eyesight. In January, Hemingway became very ill and was air evacuated to Nairobi where he was admitted to the hospital and treated for amoebic dysentary. By mid-January, Hemingway had recovered sufficiently to return to Tanganyika and resume his hunting.

■ ■ ■

When I first hunted in Tanzania, my own curiosity was piqued about where Hemingway’s safari took place. It was intriguing to try to guess in what areas exactly did Hemingway camp and hunt. For some clarification, I went to my late friend Harry Selby, the most authorative source of East African safari history I ever knew. Selby not only knew Philip Percival, but right after the war had served his professional hunter’s apprenticeship under the great hunter’s tutelage. In 1948, when Selby began conducting his own safaris, he often followed the routes he’d learned during the several safari seasons he spent with Percival.

To help map out exactly where Hemingway had hunted back then, I again read Green Hills of Africa and consulted a Tanzania map to pinpoint the places Hemingway mentions by name. He named villages such as Mto-wa-Mbu, which he spelled phonetically as “M’utu-Umbu,” and described places like Lake Manyara, where he shot ducks as well as big game.

In the first section of the book, entitled “Pursuit Remembered,” Hemingway stalks rhino on a mountain he does not name and which, at the time of his hunt, would have been quite green from the recent short rains that would have fallen a month or so earlier.

Hemingway writes of walking over foothills, through thick forests and up to high places where he hoped to find rhino: “It was a green, pleasant country, with hills below the forest that grew thick on the side of a mountain … . If you looked away from the forest and the mountainside you could follow the watercourses and the hilly slope of the land down until the land flattened and the grass was brown and burned and, away, across a long sweep of country, was the brown Rift Valley and the shine of Lake Manyara.”

In Selby’s opinion, and from Hemingway’s description, he is hunting on Losimingor, a vast mountain covered with lush mist forests interspersed with grassy glades and which is made up of a spiderweb of ridges that can only be traversed by foot. In all likelihood, Losimingor and its foothills are the “Green Hills” Hemingway had in mind when he picked the iconic title of his book.

I wrote out a list of town and village names from the book to show Selby, and he began with Mto-wa-Mbu (Swahili for “River of Mosquitoes”), which he said in his time “was a sleepy little village made up of a few Indian-owned shops called ‘dukas’ centered among a handful of native huts.” It was and still is located at the bottom of the Rift Valley escarpment, just upstream from where the river runs into Lake Manyara.

Today, Mto-wa-Mbu is no longer a sleepy village but rather a bustling and busy tourist-trading center on the much-beaten path between Arusha and the Ngorongoro Crater. If you travel by road from Arusha to Mto-wa-Umbu, within an hour’s drive from Arusha, you will pass Losimingor mountain on your right. Continuing on to Mto-wa-Umbu, you will pass right through one of Hemingway’s main hunting grounds at the beginning of his safari.

Selby elaborated about the area, saying, “Immediately after the war, in 1945, we hunted Lake Manyara and the surrounding areas (now mostly included within Lake Manyara National Park) on almost every safari. There were lots of rhino, buffalo, lion, oryx, lesser kudu, Grants and Thomson’s gazelle, waterbuck and elephant with mostly small ivory. The high escarpment country Hemingway mentioned is the western wall of the Rift Valley. The road to Ngorongoro and Serengeti winds up this escarpment and thence across the Serengeti to Ikoma and Musoma and on to Lake Victoria. We used to traverse this route frequently in both directions after entering Tanganyika from Kenya.”

From the Lake Manyara area, Hemingway moved south to Babati, stopping at a little hotel that overlooked Lake Manyara before continuing on to new hunting grounds: “From Babati we had driven through the hills to the edge of a plain, wooded in a long stretch of glade behind a small village where there was a mission station at the foot of a mountain. Here we made camp to hunt kudu, which were supposed to be in the wooded hills and in the forest on the flats that stretched out to the edge of the open plain.” Hemingway did not find his kudu there.

Selby told me he often passed through Babati with his hunting clients, which is on the main north-south road (the major artery that runs the length of Tanzania from Arusha down to Zimbabwe), whenever heading south to hunting grounds near Tabora or the Ruaha River.

“When I took Bob and Virginia Ruark on their first safari, we drove through Babati, which he also mentioned in his book, Horn of the Hunter, in connection with the missionary station nearby. It’s high, pretty country, and I presume Hemingway hunted kudu in the vicinity of the mission station which, if I remember correctly, was not too far from Babati,” Selby said.

Hemingway describes traveling even farther south: “Then we started south on the Cape to Cairo road ... through miles and dusty miles of this, and then into a valley of sun-baked, eroded land where the soil was blowing away in clouds as you looked, into … the German model-garrison town of Kandoa-Irangi.”

Selby commented that Kondoa-Irangi is the location of an old German fort that was the site of possibly the most bitter fighting during World War I’s Tanganyika Campaign, when the British and South Africans were driving Von Lettow-Vorbek’s forces south. Selby remembers the fort being pockmarked with bullet holes, and with many graves nearby—both Allies and German.

Selby continued, recalling that he had hunted all that country with many clients who collected their kudus at Kondoa. Farther east was a huge, sparsely inhabited country with very large seasonal waterholes. “One eventually comes to Kibaya, which used to be very good for big elephant,” he reminisced.

■ ■ ■

Hemingway quotes Percival as describing the country to the south as “a million miles of bloody Africa.” He writes: “After a long stretch of the million-mile country, the country began to open out into dry, sandy, bush-bordered prairies that dried into a typical desert country with occasional patches of bush where there was water, that Pop said was like the northern frontier province of Kenya.”

Selby remembered the same country, telling me that Kibaya, and for many miles surrounding that area, did resemble the Northern Frontier District (NFD), but the vegetation was of different types than that of the NFD. The town of Kibaya is 45 miles east of Kondoa-Irangi.

Eventually, the Hemingway safari arrived at “new country” near Handeni. Selby remembers the area well: “I recall a track leading from Kondoa-Irangi on the Great North Road due east to Handeni right through the country described by Hemingway. The name “Handeni” is given to the whole district surrounding the town of Handeni, which is located on the main road between the towns of Korogwe and Kilosa.”

Hemingway writes about going east into some higher country with “… timbered hills that were big enough to be mountains. These were on each side of the road … we wound our way through pleasant looking bush, up and out into the open between the two mountains and on, a half a mile, to a mud and thatched village in the open clearing on a low plateau beyond the two mountains.”

“I imagine the high country with high, timbered hills that Hemingway mentions are likely the north or south Pare Mountains,” Selby speculated.

Hemingway mentions Handeni several times in relation to the big truck going there to collect water and supplies, and writes about the impending rains, “… we must be out as far as Handeni before the rains came.”

Selby agreed that they had good reason for the concern about the onset of the rains. “The track between Kondoa-Irangi and Handeni would be impossible during the rains. There were no four-wheel-drives, remember. Commercial four-wheel-drive vehicles were not yet available to the civilian market at that time with the British Land Rover only much later introduced in 1948. Even in my day, that track was only a very primitive one, and in 1934, it would have been hardly even that,” he explained.

“On the return to Nairobi, once the Hemingway safari passed through Handeni, they would have been on relatively good ‘all-weather’ roads. So my guess from the names mentioned in the book and knowing some of Percival’s favorite hunting grounds is that the Hemingway safari route included hunting in areas near Mto-wa-mbu, Babati, Kondoa-Irangi, Kibaya and Handeni. The return to Nairobi most likely would have taken them north through the towns of Korogwe, Same and then Moshi, Arusha and across the border and back into Kenya at Namanga.

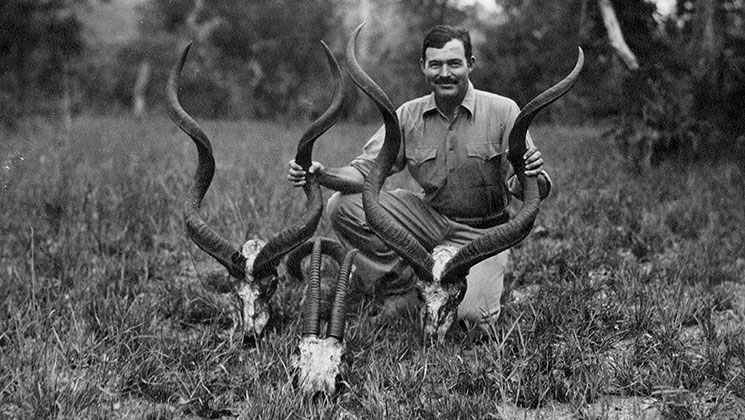

“I’m not sure how long the safari was,” Selby continued, “but Hemingway refers to being there in February and worrying about getting caught out by the rains coming up from Rhodesia, so I imagine it might have been around an eight- or 10-week safari, which was a normal amount of time for a safari back then. Judging from the pictures I have seen of Phil and Hemingway with trophies, they did collect their kudus, but never did find the exceptionally large kudu that Hemingway had hoped for,” Selby concluded.

■ ■ ■

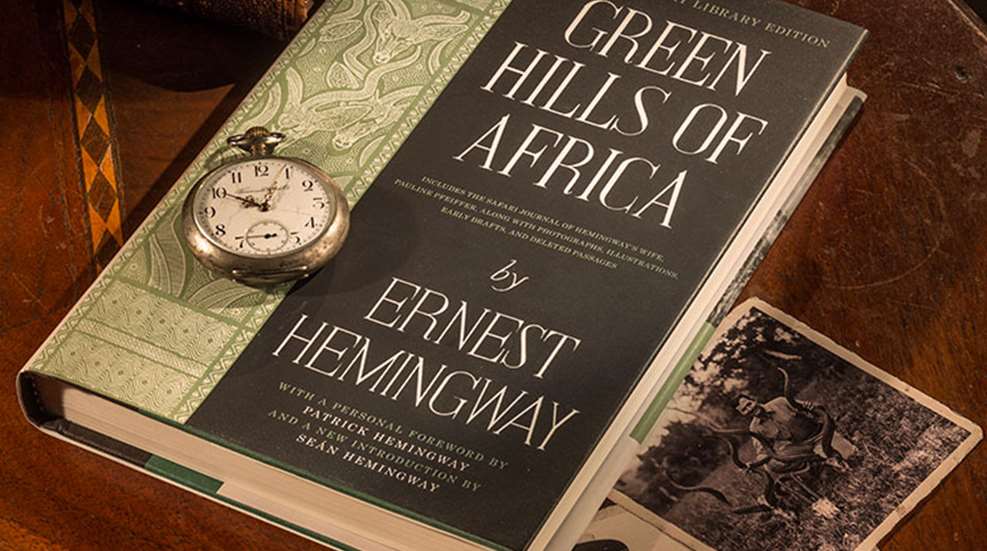

After returning home, Hemingway wrote Green Hills of Africa, which was published in 1935. The book was not well-received with many critics claiming it was not up to the standard of his previous books. Edmund Wilson, a prominent literary critic of the time, took a shot at Hemingway, writing, “he has produced what must be the only book ever written which makes Africa and its animals seem dull.”

Other critics viewed Green Hills of Africa, written while Hemingway was in his mid-30s, as an early sign of his legend overtaking his work. This depressed Hemingway, and he blamed the critics for the book’s lack of commercial success. Indeed he was so depressed by its reception that he remarked he was “ready to blow my lousy head off.”

Following on the heels of the book’s release were two subsequent “Africa efforts,” both short stories and both completely fictional: “The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber” and “The Snows of Kilimanjaro.” Both proved very popular and quickly became major highlights among his writings. Rather than feature a strong, typically heroic male character, the protagonists were married to strong-willed and often hectoring wives.

In the case of “Francis Macomber,” the story is based on an actual event about which Percival told Hemingway while he was on safari. The incident took place in 1909 during a safari conducted by Col. J. H. Patterson, author of The Man-eaters of Tsavo. During the safari, his client, a fellow British soldier, was “accidentally” killed by a gunshot, some say by his wife, others say by Patterson himself, or possibly it was suicide. Patterson’s reputation was indelibly tarnished by this affair, although criminal charges were never brought against him. A movie was made in 1947 based on Hemingway’s short story, called “The Macomber Affair,” staring Gregory Peck and Joan Bennett.

After the first safari, Hemingway always intended to return to Africa, and it’s interesting and curious at the same time that 20 years passed before he did so. In August 1953, accompanied by his fourth wife, Mary, Hemingway traveled to Kenya for his second hunting safari. He reunited with Percival, who conducted only a portion of the safari, hunting in an area of Masailand near Kenya’s Chyulu Hills, literally within the shadow of Mt. Kilimanjaro. That safari resulted in another book entitled True at First Light, written by Hemingway and edited by his son, Patrick; it was published posthumously in 1999. Hemingway also visited Uganda during that safari, where he survived two plane crashes, suffering serious injuries in the second crash that plagued him for the rest of his life. Hemingway died on July 2, 1961, of a self-inflicted gunshot.

Green Hills of Africa Reissued

Eighty years after the release of Green Hills of Africa, in 2015, a new edition became part of a series authorized by the Hemingway estate that already included reissues of A Moveable Feast, The Sun Also Rises and A Farewell to Arms. Grandson Sean Hemingway contributes an introduction, while son Patrick Hemingway, a boy at the time his parents were in Africa, shares personal memories. The book also includes photographs, early drafts of the finished narrative and a diary kept by the author’s then wife, Pauline Pfeiffer. As Pfeiffer’s diaries reveal, Green Hills of Africa was not entirely factual. The author rearranged some chronology and minimized a bout of dysentery so severe that he had to be flown out of the area. Pfeiffer’s journal also describes a near-tragedy when the author’s rifle fell off a car and fired—fortunately, no one was injured.