You’ve probably heard that African dangerous game can absorb five hits from an Abrams tank and keep on charging. You’ve probably heard that kudu, eland, wildebeest and even impala are so tough from evading lions and leopards they’ll soak up bullets that would floor a North American brown bear. Their hides are thicker, their bones tougher, their bodies drier. Their hearts and lungs aren’t even in the right places. They just don’t die easy.

Nonsense.

If African antelope are so tough, why did my wife flatten a 41-inch bull gemsbok with one 140-grain Swift A-Frame from a Jarrett custom 7mm-08 Remington? She did the same to an old blue wildebeest, kudu, red hartebeest and springbuck. All one-shot kills with the puny little 7mm-08 Remington. Shades of Karamojo Bell.

Bell was the Scottish market hunter famous for felling some 800 elephants and many buffalo, lions, etc. with the little .275 Rigby (7x57mm Mauser.) Truth be told, the iron-hide invincibility of African game is bull. It’s hyperbole spawned by a hundred years of bad bullets, bad powder, poor shooting and sensationalistic reporting. No macho bwana off to conquer Africa was going to admit his shortcomings. The animals were just too tough, the guns and bullets too small. In order to subdue African game and live to tell the tale, you had to be a real man and use enough gun!

With today’s controlled-expansion bullets, that’s no longer the case. You still have to shoot well, but do this and African plains game—from the thickest-skinned, lion-scarred warthog to the biggest eland—expires the same as all animals punched through the vitals with a proper bullet. Their hearts and lungs are in their chests. Their spines run down their necks and along their backs. Their brains lie between their ears.

This means you can drop them with something less than a .458 Win. Mag., a .375 H&H Mag. or even a .300 magnum. You’re certainly welcome to use those, but you can also shoot your .270 Winchester, perhaps even your 6.5 Creedmoor. I know Namibians who routinely shoot their plains game with .223 Remingtons and .22 Hornets. Their secret? Put the right bullet in the right place.

Their Strength is in Their Diversity

African plains game are different from North American game, but not so much in physiology as diversity. There are dozens of species and subspecies of antelope weighing from 10 pounds to 2,000 pounds. They wear coats of marvelous colors and horns of geometric magnificence. Sweeping, curving, twisting, curling, bending and towering. Such spectacular ornamentation leaves novices gawking and shaking instead of concentrating on shooting. But anyone who can keep his head in the game and shoot straight can cleanly take all African plains game with ordinary deer and elk rifles. If they use the right bullets.

I forget the exact number, but Coni Brooks, half the brains and brawn behind the success of the Barnes X Bullet line in the 1990s and early 2000s, once flattened something like 60 African antelope with as many consecutive shots. This 100-pound mother of two used a rather big cartridge for the job, a .338 Winchester Magnum. Well, if that tiny woman could do it …

During my first adventure to Zimbabwe in 1995 I enjoyed similar results with a similar cartridge, a .338 Dakota spitting 210-grain Barnes X bullets. Just 14 of them accounted for 12 animals from duiker to eland. Two shots were just finishers. In subsequent safaris I had similar success with the .325 WSM, .300 Winchester and Weatherby magnums, .30-06 Springfield, 7mm Remington Magnum, .308 Winchester and even a .243 Winchester. Bullets varied from the Barnes TTSX to the Swift A-Frame and Scirocco, Winchester Ballistic Silvertip and XP3, Hornady GMX and SST, Norma Oryx and Kalahari, and Speer Grand Slam. All of these projectiles in the chests of African game led rather quickly to its demise.

These days I regularly hear about similar performance from friends and acquaintances who have dared safari with their deer and elk rifles. So perhaps we should pry a bit deeper and figure out what’s going on …

How Bullets Terminate African Game

First, we should understand how bullets extinguish an animal’s life force. Sometimes they appear to do it like a boxer’s knockout punch. Wham! And down goes Frazier. This is all about the central nervous system. Rattle it hard enough and the nerve center, the brain, shuts down. Sometimes temporarily, sometimes permanently. This can be done with a brain hit, most obviously, but also with a spine hit from the withers (above the shoulders) forward. Sometimes it happens when a high-velocity bullet dumps all its kinetic energy in the heart just as it’s pumping and blood pressure is maximized. This is Roy Weatherby’s famous “hydrostatic shock” theory at work. All evidence suggests this generates shock waves sufficient to disrupt or erupt blood vessels in the brain.

Such knockouts are appreciated when you get them, but a safer approach—because the target is larger—is to take out the pumping station. The heart and lungs are vital organs, but smacking them solidly—either with a heavy, dramatically expanded bullet that passes through or a high-velocity bullet that “explodes” to create a massive wound cavity—does not mean the animal will always expire instantly. Most of the time it does not, regardless of the bullet’s mass or velocity. Animals, including humans, can live for several seconds without a functioning heart or lungs. Both organs work to provide freshly oxygenated blood to the brain. This is essential for keeping delicate brain cells alive. Disrupt this operation and, as blood pressure drops, an animal grows dizzy and faints. If oxygen to the brain isn’t restored, brain cells die within 10 minutes. Break out your skinning knives.

This explains why a heart-shot whitetail—or black wildebeest—often runs madly for 50 to 100 yards before falling. Its brain is still perfectly functional, and it says “flee.” I once put a 180-grain .308 bullet at 3100 fps through a kudu’s heart. It leaped and ran as if I’d merely shouted “boo.” After 60 yards, its blood pressure plummeting, it dizzied, wobbled, crashed into a tree and fell over. I’ve seen elk do the same thing.

There’s nothing magical about African plains game. They wear no force shields. Physiologically, they function just like deer, elk and moose. Taking them cleanly doesn’t require “enough gun.” It requires good bullets.

Bullets for Africa

The first time I hunted buffalo my professional hunter asked what bullets I’d brought. When I said Barnes TTSX, he said, “Perfect. They’re like a soft-point and solid in one.” That’s as accurate a description of a good African game bullet as you can get. You want a slug that opens 1.5X to perhaps 2X while retaining enough shank mass behind this expanded nose to continue driving forward. The bullet must be hard enough to resist breakage against major muscle and bones, but not too hard. Too much expansion and friction stops penetration. Too little expansion and bullets sail through like target arrows, inflicting insufficient tissue destruction and trauma.

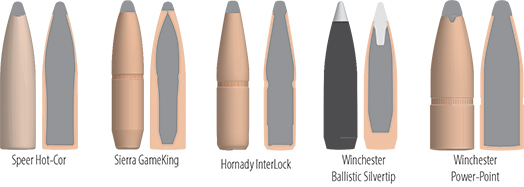

Cup-and-Core

Traditional cup-and-core bullets (a lead core pressed into a gilding metal or copper jacket) tend to expand excessively or break into two or more pieces. This reduces penetration. One solution is harder lead. Another is a thicker jacket or softer (pure copper) jacket. Yet another is a small, inner ring of jacket. Examples include Sierra GameKing, Nosler Ballistic Tip, Remington Core-Lokt, Hornady InterLock, Speer Hot Core, and Winchester Power Point and Ballistic Silvertip.

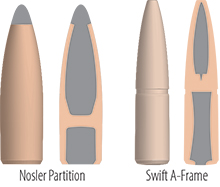

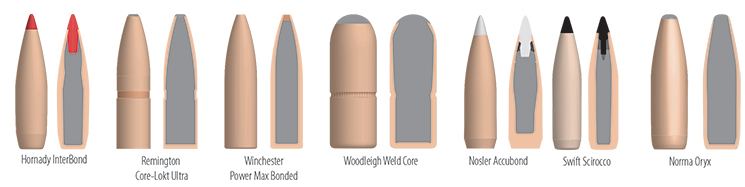

Partition

The Nosler Partition ensures sufficient shank mass by putting a transverse wall of jacket material between it and the nose lead. The nose expands and can break away like a traditional cup-and-core, but the shank lead keeps driving. The Swift A-Frame uses a similar design, but with a thicker, pure copper jacket and bonded lead nose.

Bonded

Bonded bullets combine gilding metal or copper jackets welded to the soft lead core. This prevents core and jacket separation. Soft lead can still expand excessively and be eroded by contact. Examples include Nosler Accubond, Hornady InterBond, Swift Scirocco, Norma Oryx, Woodleigh Weldcore, Remington Core-Lokt Ultra Winchester Power Max Bonded.

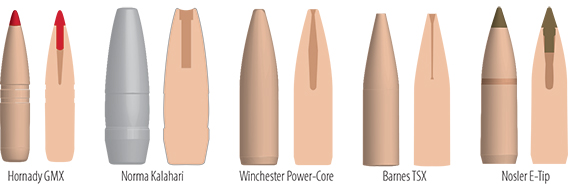

Hybrids

Federal’s Trophy Bonded Bear Claw blends a bonded lead nose to a thick copper jacket too, but keeps the shank solid copper. The Trophy Bonded Tip adds a sharp, polymer tip to the nose. The Barnes MRX keeps the all-copper nose, but fills the shank with tungsten-based Silvex.

Monolithic

These skip the lead in favor of all copper or gilding metal. Expansion is achieved via a hollow “expansion cavity” in the nose, often behind a polymer tip. On impact, hydrodynamic forces drive into the hollow and slam the walls outward, creating an expanded cup or several wings or petals that churn as the long, solid shank drives them forward. Examples include Barnes X series, Hornady GMX, Nosler E-Tip, Winchester Power Core, Norma Kalahari, Remington Copper Solid and Cutting Edge. Some nose petals are made to shear off after initial penetration and tear tissue beyond the main bullet’s path.

How to Choose

Depending on their biases and experiences, African PHs generally love or hate various cartridges and bullets, so take their recommendations with a grain of salt. But take them. Then balance them against your own observations on bullet performance on North American game. Any cartridge/bullet you’ve found effective for deer should more than suffice for similar-sized and smaller antelope including springbok, impala, duiker, steenbuck, blesbuck, sitatunga, reedbuck, puku, red lechwe and bushbuck. Cartridges and bullets you like for elk and moose will handle oryx, hartebeest, blue and black wildebeest, kudu, waterbuck, sable, eland and zebra.

Of course, larger bullets and calibers are never a bad idea. The zebra, eland and bongo are especially good excuses for a .338, .35 or .375, .40 or even a .416. There’s no such thing as too dead. But there is such a thing as over-gunned. Regardless how deadly and powerful a rifle/cartridge is, if you can’t control it, you lose. A miss is as good as a mile and a flinch is a good way to miss.

Given the time and expense you invest in an Africa safari, you certainly want to use enough gun. Just remember it’s not the gun or even the cartridge so much as the bullet that determines outcome. More African game has been missed or wounded and lost due to unfamiliar, heavy-recoiling rifles than to familiar, light-kicking rifles the hunter trusted and knew how to control. With the right bullet, of course.