I woke to the mesmerizing sound of raindrops pattering down on the metal roof. It was warm in bed, and I knew once I crawled out of my cocoon it was going to be the last warmth I felt for a while; the day would be wet and cold. After some quiet deliberation, I finally took the first step, climbed out of bed, started the coffee and dressed for a day in the wet Oregon fall weather. While hesitant to leave the warmth of my bed, it was hard not to be excited for the conditions Mother Nature was providing for my blacktail hunt. Blacktails and rain … like peas in a pod.

Oregon’s blacktail deer season generally begins the first weekend in October, and runs through the first Friday in November. While many people, myself included, hunt at the beginning of the season, the real magic happens during the last week. While each year is different, generally the weather in the first part of October is pretty nice, often sunny and warm. These are not the best conditions to find these secretive deer, but as the month wears on, the weather begins to change, and we often have the first of our major fall storms roll in. These storms, along with the looming deer rut, dramatically increase the chances of finding a nice blacktail.

It’s been said many times that a trophy blacktail is one of the hardest trophies to collect, and after having hunted them for the last 27 years, along with mule deer and whitetails in many other states, I can attest to the truth of this statement. A lot of this comes down to the terrain they live in: Western Oregon, especially the northwest portion of the state, is an incredibly thick temperate rainforest. Combine the thick natural cover with a deer that is a secretive homebody, and that’s a recipe for an animal that can be extremely hard to root out of his natural home. Blacktails live in an incredibly small home range, often spending most of their lives in an area smaller than half a square mile, especially in the northern part of the state. Moving farther south through Oregon, the home ranges can become a bit larger and creep close to a square mile, and in the far southern range sometimes close to 3 square miles, but for the most part these deer qualify as true homebodies. The one exception to this small home territory are blacktails living in areas that receive decent amounts of snow, causing them to migrate both spring and fall.

Let’s look at that a bit closer. A square mile is 640 acres of land. Many of these deer never leave an area that size or substantially smaller, so think about how well they know every nook and cranny in their own back yard. It begins to explain why at times they can be so downright frustrating to find. Add to that the shear amount of cover in the tight confines they call home, and the reality begins to emerge: A blacktail trophy can be one of the toughest of all deer species to collect.

Biologically, blacktails have evolved to use this dense cover to their full advantage. While they can occasionally be found in the open (especially during July and early August), they are never far from substantial cover, and most often they spend their entire time in heavy cover with only small openings here and there.

Anyone who’s hunted these animals for any time at all can relate stories of walking within mere yards of blacktails that either blow out practically at their feet, or often let the hunter walk right on by if they think they haven’t been spotted.

A few years ago I’d finished my morning hunt and was walking back to my truck. I was walking below a fairly new clear-cut, and knew there was a road running through the middle of it that would get me to my pickup even faster than continuing along the road I was using. I decided to cross through the cut itself, and as I made my way up toward the upper road, I came over a little lip onto a small bench (classic blacktail hangout). As I passed a massive old stump, I caught the slightest flash of movement. I popped my head around the other side of the stump, which was as big as a small car, and I saw a fantastic 3-point making a beeline for the timber only 30 yards away. The cagey buck managed to put every single stump in the cut between us, allowing him to gain the cover before I, the flat-footed hunter, ever had a chance to get off a shot. That buck had let me come within 5 or 6 yards before deciding I was too close. Never assume while in the blacktail woods that just because an area is visible a deer isn’t managing to hide close by, sometimes almost in plain sight.

Oregon Geography

The Cascade Mountain Range separates the western third of Oregon from the rest of the state. This huge range lies about 100 miles from the Oregon Coast, and rises from the Willamette Valley floor to elevations of 6,000-7,000 feet, with some notable volcanic peaks rising to almost 12,000 feet. This steep rise of mountains blocks the eastward-moving storms that roll off the Pacific Ocean, and wrings out almost all the moisture they carry on the landscape to the west, creating the lush temperate rainforests for which Oregon is known. What many people don’t know is that two-thirds of Oregon is high-mountain desert, thanks to all the moisture that doesn’t make it across the Cascades.

There is also the Coast Range, which runs north to south along, amazingly enough, the full length of the Oregon Coast. This range of mountains also wrestles a fair amount of moisture from the storms that continuously roll eastward off the Pacific from fall through spring. This makes the coastal region even more lush and thick than the area west of the Cascades.

In the northern half of Oregon, the lush Willamette Valley, the namesake of a major river and tributary of the mighty Columbia, separates the two mountain ranges. Portland, Ore., lies at the far northern end of the valley at the juncture of the Willamette and Columbia rivers, and Eugene lies at the southern end.

To illustrate how much moisture the two mountain ranges actually extract from these Pacific storms, understand the town of Tillamook, located on the Oregon coast, receives approximately 90 inches of rainfall annually, and the town of Welches, located at the base of the Cascade Range, receives 87 inches. Contrast this with Portland’s annual rainfall, which is just less than 40 inches per year, and it’s easy to see how these temperate rainforests are created.

From Eugene south, the foothills of the Cascades begin to blend with the Coastal Range, and at the south end of the state, the Siskiyou Mountains bridge the two ranges. Since this section of the state is less dominated by a wall of mountains, it’s more arid than the mountain regions to the north. As an example, Roseburg, Grants Pass and Medford all receive around 30 inches of rainfall each year, although sections of the Siskiyous, the Coastal Range along the southern Oregon coast and the crest of the Cascades still see considerable rainfall, anywhere between 75 to 100 inches annually.

This means there is a diversity of terrain in Oregon in which blacktail deer thrive. At the northern end of the state the landscape is primarily thick temperate rainforest, with a lush valley in between, and lots of agriculture mixed with broken cover and some patches of conifer forest. To the south, the Coastal Range remains a verdant rainforest, but the interior mountains become much more arid. They often exhibit thick cover on the north-facing slopes, while the southern slopes can be more open, often containing stands of oak trees and manzanita, instead of the conifer forests that abound in the other portions of the blacktail’s range. At the southern end of the state, the majestic Siskiyous can again be a mixture of thick conifer forests, while sometimes exhibiting some of the more open south- and east-facing slopes.

The Cascade Range is also a rainforest along its entire length, but as it’s impacted by significant snowfall the deer that live there are migratory by nature. These deer often migrate up into these mountains as the snow recedes each spring; some of them even reach all the way into the alpine reaches of the range. In the fall the migration is reversed, with deer migrating off both slopes of the Cascades, moving to the lower reaches on each side of the mountains.

This is a great place to mention the actual range of the blacktail deer. The Columbia blacktail ranges from British Columbia through Central California. The Cascade Range in the northern portion of their range, and the Sierra Nevadas in the southern portion are considered their eastern boundary. There is some crossover of the blacktail’s range with the mule deer on the eastern sweep of these imposing mountain ranges. Since these deer are related, and readily crossbreed, an interesting cross (often called bench-legs) can often be encountered when hunting the eastern slopes of these ranges.

This is also why record books don’t allow blacktails from much of the Cascades and Sierra Nevadas to be scored as true blacktails. There is too much probability of these animals blending their gene pools, although most hunters in Oregon consider most any buck killed on the west slope of the Cascades to be a true blacktail.

Compact Racks

When hunting blacktails for the first time, it’s imperative to understand what really constitutes a trophy animal. Blacktails are a diminutive cousin of the mule deer in the antler department. I like to compare their rack size the same way I might compare a Coues deer to a trophy whitetail: While they have many similar characteristics, the Coues deer is much smaller in the antler department. The same relationship can be said to exist with mule deer and blacktails: Their antlers might have similar characteristics and shape, but overall, blacktails are much smaller. A 170-inch mule deer buck might be a nice public-land trophy, while an exceptional blacktail might score only in the 130s to 140s.

Blacktails also don’t often exhibit perfectly symmetrical racks. They certainly can, but it’s also common to see deer with mismatched points, and often, a mature buck might only be a 2x2, 3x3 or some other combination of points. As Jason Rice, a long-time hunting guide operating out of Roseburg, tells his clients, “It’s all about the frame.” A quality blacktail might only be 18 to 20 inches wide (sometimes even narrower), and might not carry four points per side. I’ve seen some studies where mature 4-, 5- and 6-year-old and sometimes even older deer where only 2- and 3-point animals, although they commonly exhibit a lot of mass.

Still-Hunt Slower

Just like many other dyed-in-the wool blacktail hunters, still-hunting might be my absolute favorite way to pursue these cagey animals. Slipping quietly through the Northwest woods can be relaxing, and occasionally it can be interspersed with moments of sheer adrenaline-pounding excitement. In my opinion, there is also no more challenging way to attempt to take one of these elusive yet majestic animals.

When still-hunting, especially considering the blacktail’s tendency to let hunters get very close, moving slowly is of paramount importance. When I say “slow,” I can’t emphasize enough how slow. Blacktails have a tendency to hold incredibly tight to cover, and when they do decide to move, the thick cover they live in often allows them to slip away without ever being seen. It’s like trying to root out a sniper in a ghillie suit from his hide: The only way it’s going to happen is to move incredibly slowly.

I read a great description in one of John Gierach’s books that still-hunting was the act of hunting in motion, while not moving. I can’t think of a more apt description: slow-motion, while being perfectly still. If you can visualize that, it might be easier to get a handle on the speed required to be successful with this technique.

Now imagine moving exceptionally slowly through a section of forest, and then go half that speed—and that still might be too fast. There is literally no way to move too slowly while using this technique. The idea is to move so slowly that every single piece of cover can be examined extensively, visually breaking down all of it. When methodically searching each piece of cover, an entire deer will hardly ever be spotted. It’s more common to spot an antler tip, leg, shiny nose, an eye, or other irregular shape or color, and then upon further inspection, as the detail is studied, an entire animal appears attached to the irregularity that was originally spotted.

A few years ago, I was slipping down an overgrown skid road, moving slowly while picking apart all the cover around me during an ever-present downpour. As I was painstakingly searching through the twisted brambles of an alder patch with my eyes, I caught a glimpse of a white patch that just didn’t look like it belonged. As I continued to stare at it, I eventually made out a nose, then an eye, and then all of a sudden an alert 3x2 buck materialized out of the cover, watching me intently from a mere 25 yards away. He was frozen in place, not moving a muscle, but very aware of me. We stood there for 10 minutes in a staring contest, until I took a step forward (having decided early on that I was looking for a more mature animal), and he silently turned and quickly disappeared into the thick cover surrounding us both.

When still-hunting slowly enough, this is a common occurrence, finding deer exceptionally close. Sometimes deer are spotted before they can spot the hunter; although I’ve never caught a mature deer flat-footed when hunting this way. This is another reason rainstorms are such a boon for blacktail hunters: The rainfall masks sound and movement, enabling a hunter to stalk right into the blacktail’s living room.

The kind of cover you still-hunt should at least have enough openings to see 20, 30 and occasionally 50 yards or more. The more open the terrain, the better the opportunity to spot the animal first. However, in my experience, many hunters begin speeding up when they hunt these more open areas, since they wrongly assume they can see much better, and would obviously spot any animals in the area. This is a huge mistake. The deer will either depart before being spotted or they will choose to let the hunter pass. The only way to combat this is to again move as slowly as possible. It could take an hour to cover 100 yards, and that wouldn’t be too slow.

My own still-hunting epiphany occurred late one fall when I had the luxury of hunting during an early snowfall in an area I’d hunted many times before. In Oregon, we don’t often see snow during our blacktail season unless hunting high in the Cascade Range, so this was truly a blessing. What was more surprising was the fact that I was consistently cutting new tracks, even finding them crossing my own tracks as I returned to my truck in the afternoon for a lunch break. As I sat in the warmth of my cab contemplating why I was seeing so many fresh tracks, but not seeing any animals attached to those tracks, I concluded the problem had to be that they were seeing me before I saw them. I figured the only way to combat this problem was to begin moving tremendously slower than I had already been moving.

I left my truck that afternoon and began diligently moving at a snail’s pace. I slowly took a step then stopped as described above, using my eyes to search through all the details surrounding me. Within the first 100 yards of slowing down to this virtual crawl, I spied a doe feeding contentedly 20 yards off the trail I was working. Holy cow, I thought, moving this slow actually works!

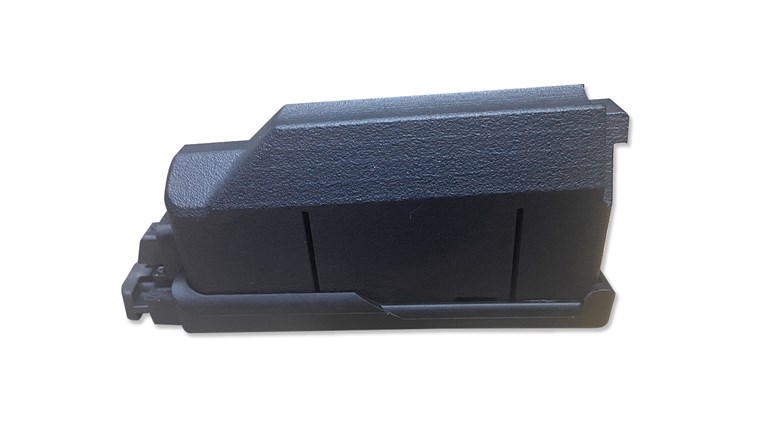

Using this new, incredibly slow pace, I began to see deer with regularity, and bumped two respectable bucks without getting a shot. Late in the afternoon as I continued using my newly discovered, and much slower still-hunting technique, I caught a flicker of movement on a side trail. I watched intently as a very respectable 4-point emerged on the trail, trotting along with his nose down, obviously trailing a hot doe. He was just what I had been looking for, and as I slowly raised my rifle, he stopped to see what the motion was. He never took another step, as I anchored him right there. Success! Still-hunting at an absolute crawl was the link I had previously been missing.

Finally, it also goes without saying that keeping the wind in your face is mandatory when utilizing this technique. I always keep a bottle of Breeze Squeeze in my jacket pocket, and it often stays in my hand when I’m hunting through thick stands of cover. I’m constantly checking the wind to make sure it’s in my face. Failure to mind the wind simply means game won’t be seen. Deer can be tolerant of some noise, and even the actual sight of you slipping slowly through the forest, but at the first whiff of man you can bet they’ll make a hasty retreat.

Spot More, Stalk Less

This is another very popular technique, although it’s one often done incorrectly from the cab of a truck! It’s not uncommon to see trucks rolling slowly from clear-cut landing to landing, stopping long enough to disgorge several hunters who quickly scan a clear-cut with their binos then hop back into their vehicle and roll to their next opening. Amazingly enough, this sloppy technique does account for its share of animals (although they are most commonly juvenile bucks). But if spot-and-stalk is utilized correctly, it can be one of the most deadly efficient ways to tag an Oregon trophy.

When hunting with clients in the Roseburg area, Jason Rice explains the best way to utilize spot-and-stalk: He picks a spot based on current conditions (wind direction is key) where he knows deer are likely to move, and literally sits on a single spot for an entire morning or evening. This is key: Have faith in the spot, and stay in one location for an entire hunt period while continually glassing the area. It’s important to not give up when animals aren’t immediately spotted, and to stay with the game plan, and for heaven’s sake, don’t put down that binocular!

When glassing, pick apart each section of cover, just like when still-hunting. Glass in grids, and keep intently looking for anything irregular. An entire animal is hardly ever spotted. Often only a small bit of detail will be spotted, and by studying it, more of the animal is eventually seen. Rice says when glassing, eight out of 10 animals are picked out of cover, while a few will feed in or out of the openings, but it’s generally does or immature bucks that are spotted on the move. Rice also adds that it could easily be the 600th time he’s looked at a piece of cover when suddenly he detects the flick of an ear, or possibly an antler tip showing above the cover. Then, by carefully studying the detail, he is able to make out an animal that might have been bedded there all along.

One thing Rice is adamant about: Don’t get overly excited when finally spotting an animal, and don’t forget to look long and hard enough to ensure the location is positively marked. At times he, along with his clients, after spotting a deer, have immediately dropped their binos to switch to a spotting scope, and then have had an exceptionally hard time finding the animal again after failing to make sure they had the spot firmly pinpointed. Make sure and mark that spot.

Rice is also a very dedicated "fog hunter." Deer living in tight cover have three basic senses that keep them safe: hearing, smell and sight. If a fog bank rolls in, it will be extremely hard to spot deer, but the animals will have just as much trouble seeing. They will rely solely on their sense of hearing and smell, so will likely not move much when fog descends on the area. Conversely, as soon as the fog lifts they’ll move, even if it’s the middle of the day. So when trying to glass a spot and the fog rolls in, sit on it; don’t move, and don’t get impatient and leave. Sit it out, and be ready to diligently glass when it breaks. According to Rice, it’s like clockwork: When the fog lifts, he begins to see deer movement almost immediately, regardless of the time of day. While many hunters may go higher or lower, trying to find areas not impacted by fog, Rice has found sitting it out is often key to locating some great animals.

Hunt familiar ground. Select a spot where animals have been seen before, then have faith they are there and stay behind the glass. Don’t give up when deer aren’t spotted right away; keep picking apart the cover. Rice recommends finding places like open draws with interspersed cover, especially stands of Himalayan blackberry and poison oak. Feeding areas or other likely little hidey-holes are also a good bet, but they should all share a common denominator: close, heavy, mature cover. Very seldom will a mature buck be caught far away from an available refuge.

Due to the nature of the vegetation and terrain, moving closer isn’t always an option, so sometimes the shot will have to be taken from where the deer is spotted. It’s a good idea to be ready to shoot 200-300 yards, and to be confident shooting as far as 400 yards.

Ideally, when spotted the animal will already be bedded. If one is seen moving, wait until he beds down before making a move. It’s much easier to make a move on a deer in a known position than one that’s moving while you try to stalk.

Stands Work, Too

Since blacktails are so cover-oriented, placing a stand overlooking small openings in feeding areas can be a great way to put a tag on an outsized buck. Trail intersections, and routes between feeding and bedding areas are also likely spots in which to place a stand.

Treestands are the most common, followed by ground blinds. The nice thing about treestands is they give a hunter a better bird’s-eye view of the terrain. They also help disperse scent in the thermals up off the ground. While this doesn’t mean minding the wind still isn’t deadly important, it can help manage scent dispersal. The best plan, though, is still selecting a stand location where the wind will be in your face.

While ground blinds don’t give a hunter carte blanch to move freely, they certainly help mitigate small movements. The other nice thing about them is they are often waterproof, helping keep you dry and out of the nasty weather that often pervades the last couple weeks of Oregon’s season. This can be the difference between sitting for only an hour or two and hunting an entire day. As the rut looms toward the end of the season, bucks begin cruising for does, and can be moving any time of day.

A well-worn trail moving to and from bedding and feeding areas can be one of the best locations for a stand, especially later in the season as mature bucks actively search for receptive does. As the rut begins to ramp up, bucks begin ranging out of their core areas searching for receptive does. Hanging a stand on a spot where there’s lots of deer traffic is a good bet. Look for areas with lots of recent sign. Even better is an area with frequent rub lines along these travel routes.

Majestic Challenge

Blacktails can get under your skin. These deer have all the ingredients of an exceptional quarry. Striking good looks with their often-dark skullcaps set against a gray/white face and buckskin cape with compact heavy antlers—they simply look majestic. They are as challenging an animal to hunt as you’re likely to find in North America. They have definitely managed to captivate me for the last three decades. If you come out to Oregon to try to find the “Ghost of the Forest,” be prepared, because he might just get to you, too.