When the turkey gobbled, that all-too-familiar public-land dread ran right down to my boots—yeah, I was worried some other hunter might hear the tom. I pushed hard up the mountain in the quarter-light of a clear May morning a half-hour before sunrise. Not far above, the gobbler was standing on a limb with a panorama of mountains green with half-grown leaves below his throne.

Two more gobblers began their chorus farther west on the mountain but along the same topographic line. I glanced at the map on my glowing GPS screen to mentally note where they were and kept climbing, assuring myself no one could possibly hear the tom from the dirt public road below. The roar of a freestone stream running beside the road, a cold and fast creek fed by brooks tumbling down the mountainside, drowns out all the sound from above.

A map led me to this spot, not gobbling. Topographic maps, you see, are like treasure maps in that they have hidden clues that can lead to turkeys if you know how to read them. A topo map showed access points to public lands along the dirt road. Just above the road, elevation lines almost joined into a thick black band on the map, a formidable barrier dense with saplings and strewn with boulders.

Above this steep mountainside, however, the map showed an opportunity. Just 400 yards straight up was a mountain bench—mostly level ground a few hundred yards deep and nearly a mile long. Springs seeped from the mountain on this bench, wetting the ground enough to topple trees and keep meadows open on a southeast-facing slope. But the bench was too small, and the canopy too thick, for this opportunity to be clearly seen on aerial photos—Google Earth is an awesome and free tool, but it is hard to see spots like this without topo lines.

Still, I thought this spot too obvious until I scouted it and heard the stream. I knew hunters like to scout by calling before the season from trails and roads. I also knew they wouldn’t hear a thing from the public road in this tight valley.

The tom kept gobbling. Damp leaves squished underfoot, and I grabbed saplings as if they were walking sticks to hoist myself up. The forest is public and vast but only 100 miles from the honking taxis and rushing people of Manhattan, all so oblivious to this moment of triumph and failure, as one of us must win and the other lose. I thought of a line from William Faulkner’s “Big Woods”: “Now a man has to drive two hundred miles to find enough woods to harbor game worth hunting.” I knew, thanks to sportsmen, some things are better now.

When the ground leveled I set up 200 yards from the gobbler but along the same topo line he was roosted on. Sure, I’d have slipped closer than 200 yards in different terrain, but up there the forest is old and the hardwoods open in early May. Also, the thing about these big-woods gobblers is they’ll come running, sometimes from a long way if they don’t have hens. This is especially true if you are on the same topo line along the mountain as they are or are slightly above them.

When they hit the ground, though, their gobbles can be deceiving, as the acoustics of the topography on mountainsides can make them sound much closer or farther away than they actually are. This is another reason why you shouldn’t just study aerials to find overlooked gobblers, but should also have a GPS with topo maps uploaded or use an app that gives you access to topo maps on your smartphone. You need to be aware of the obstacles between you and a gobbler. A topo map can show you these, but aerial photos might not. On mountainsides, where the lines make a “V-shape” for example, you know there is a ditch or stream. These are often thick with vegetation and have steep, eroded banks that can make a tom hang up.

The gobbler answered the first few soft yelps I made. The spring world seemed to descend below us in greening forests and fields in the soft distance. The dampness of the thawed ground was alive with the odor of damp leaves and fresh, growing grass.

Soon a muffled gobble told me he was on the ground. He was coming with his red neck stretching, hunting for the hen. And soon another lovely public-land hunt was over in that melancholy celebration a successful hunt always leaves us with.

Before going back down the mountain I marked the gobbler’s roost location on my GPS. By following the topo lines across the mountain I could see other roosts I’d marked along this same line. Some were 200 feet higher, but that’s as high as they go. Turkeys only go so high in the mountains, as they follow spring up the slopes. Finding what I call the “turkey line” on topo maps in the East or the Rocky Mountain West allows you to follow a line as you call to locate toms after they fly down. This way you’ll know you’re either on their level or just above them.

Though a lot of public turkey hunting spots are mountainous—from Vermont’s Green Mountains down Appalachia to Georgia and in much of the West—topo lines can also show overlooked hotspots in bottomlands. Here are four more real turkey hotspots on public lands (well, all but the GPS coordinates) that you can use as keys to look for your own hotspots.

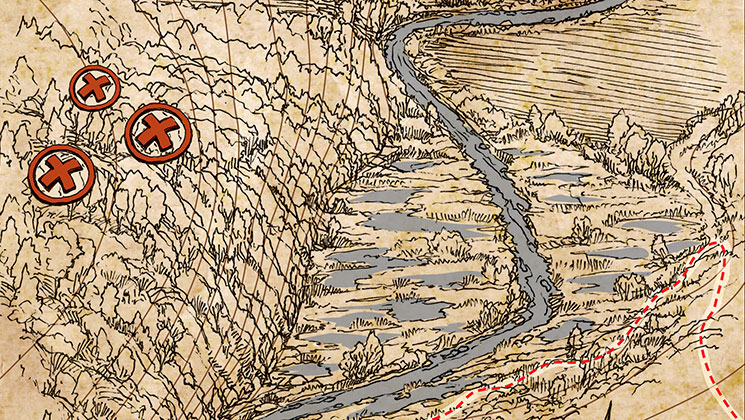

THE OVERLOOKED CORNER

THE OVERLOOKED CORNER

How to Find this Spot

If there are hiking trails in the public area you hunt, get a map of them. Now grab your topographic map of the area. The map can either be paper or one you can alter with mapping software. Mark the public parking spots on the map with one color. Next, draw in the hiking trails with another. This will show you how most hunters will access the property, and from where they’ll call and listen. Look at the topo lines to see how the roll of the terrain will let them hear some gobblers, but where the hills will make others hard to hear. Now follow the edge of the public land around the map looking for areas the trails don’t go.

I used this strategy to find what has been a go-to spot for me for a decade. Every year I am pleasantly surprised that no one else has found it, even though it’s plain when you map it out. This spot lies in a back corner of a large forested public area. A hiking trail ends at a swamp; just over the swamp are huge private farm fields. But just west of where the trail ends is a swamp and a small cliff. Over the cliff is a 100-acre section of hardwoods torn up with turkey scratchings that ends in a steep mountainside.

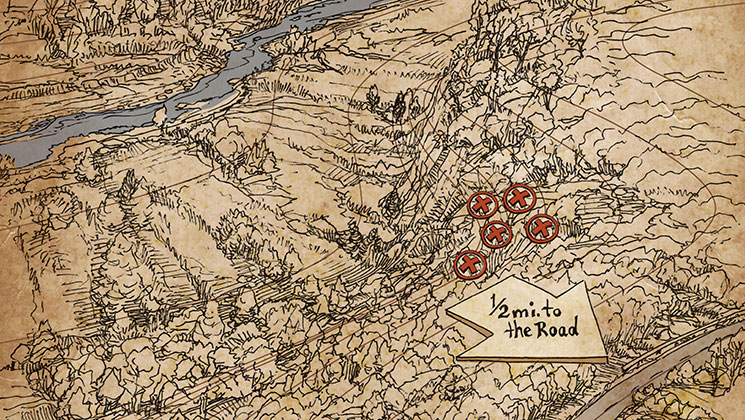

How Toms Use It

This is primarily a roost area (marked with red X’s on the map). There are huge white pines and mature oaks up against a steep ridge. The cliff makes it hard to hear the toms in this section even as they gobble from their roosts, but there are usually six to eight gobblers in the spot at first light. Most of the turkeys quickly go to the fields on private ground where the toms strut. Some move up the mountain after flying down.

How to Hunt It

I’ve killed six gobblers in this spot, all with different strategies. The best tactic is to get on their topo line at first light, but not too close. I’ve gotten too close here and watched them, after gobbling hard from the roost, simply fly away to the fields. I was so close they figured something was wrong, as they couldn’t see the hen.

This is a roost area, so moving around after daylight must be done with great caution until the birds leave. Setting up 100 yards from them in spots they naturally use to navigate to the fields has been the most effective strategy.

THE HIDDEN GEM IN A SWAMP

THE HIDDEN GEM IN A SWAMP

How to Find this Spot

“Come on, we have to move”—and we were off, me following his camo back into alligator swamp water. Some steps let the black water drip over the rims of my rubber boots as all my thoughts pondered the alligator we saw lying in the shallow water in the headlights on the way in.

We stepped out of the black water and pushed into brush, all just leafing out, and then a few feet up to oaks on what he called a “ridge,” but that only rose a few feet above the Alabama swamp. And then back into another swamp—and me holding the shotgun at port arms to blast a hole with No. 4 shot into any gator that dared have a go at me—and then up to another “ridge.”

At the fifth rise we stopped and sat with our backs against big trees. He sucked on a wingbone call. Boom! went a gobble just 100 yards away.

How Toms Use It

He nodded, whispered, “Thought they’d take this ridge. Few hunters come in here because they think it’s all swamp, but there are high points the turkeys use as strutting areas and highways.”

Soon we saw glowing red heads bee-bopping down a deer trail along the ridge. The only trouble then was not shooting more than one, as three gobblers were all lined up.

How to Hunt It

Sure enough, when I looked, I saw that the topo lines show rises of 10 feet like ripples in the swamp. The ripples lead from roosting areas on higher ground to large, private green fields. Though we had access to the private ground in this case, the best hunting was on the little ridges on public lands.

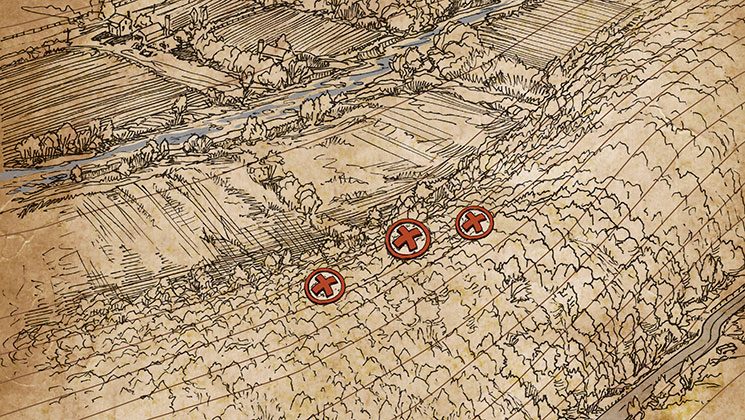

THE SECRET CORNER

THE SECRET CORNER

How to Find this Spot

When most hunters enter a public area, they naturally want to get away from the roads and houses on nearby private lands. That makes sense, but it also makes many overlooked hotspots. Often the best hunting for deer or turkeys is on the public land running just behind a farm or even a housing development.

I found such a turkey hotspot by following the property line first on a topographic map and then on foot. This one is the back of a ridge that descends into a deep, swampy ditch with a muddy stream at its bottom. Just across the stream are farm fields and a housing development. If the farmer or the people who own those homes were into turkey hunting the spot wouldn’t be much good, but they clearly aren’t. Also, because the ridge faces private land the turkeys that roost on it and gobble from it aren’t easy to hear from the public land.

How Toms Use It

Turkeys roost on the ridge and either fly over the muddy ditch to strut in the fields or fly down on the ridge and use a few game trails to cross the ditch and pop out into the fields.

How to Hunt It

At first I tried getting on the same topo line as the toms on the ridge, but their hens and their travel pattern always took them quickly away toward the fields. They’d gobble to me from the private land but the muddy ditch was too much of an obstacle to call them across it. The solution was to get in early and sit right on the property line in the few spots where they cross the ditch. Early in the season they can be called to these crossings. Later in the season it’s more effective to stand hunt, as the toms that survive do get called to a lot from the public ground over the top of the ridge.

THE CANYON

THE CANYON

How to Find this Spot

The acoustics of this place on public land in Colorado protect it from hunting pressure. This spot is located along the Front Range and just off a popular gravel road. The thing is, you can’t see the terrain or even hear the gobblers from the road. A topo map, however, makes it obvious. Just over a summit and down 600 feet is a canyon shaped like an amphitheater with a stream at its bottom.

How Toms Use It

Turkeys roost in tall pines at the top of the canyon. The roost is only a half-mile from the road but the steep, rocky cliffs shaping the amphitheater ricochet their gobbles away from the road located far above. The turkeys fly down and walk along the canyon bottom away from the road to a broad valley that is a monstrous hike from the road.

How to Hunt It

Before first light you need to drop down a side ridge as you watch your map. When you go down far enough to avoid the cliffs around the top of the canyon you turn into it. When the toms begin gobbling the sound is terrific as the Rios’ gobbles echo off the canyon walls. Soon they’ll fly down and march along the canyon bottom and the stream to lower ground to strut and feed.

Closely following topo lines in the Rockies will also save your legs. Too often Eastern hunters want to head straight for a gobbling turkey. But a beeline will often mean steep descents and hard climbs in thin air. It’s often better to follow the contour lines around to get to the tom.

Reading topographic maps is becoming a forgotten skill as so many of us are swooned by high-resolution aerial photos seen on our smartphones. Aerial photos are useful and important, but reading contour lines is still a great way to find overlooked turkey hotspots.

Turkey Map Tips

Pinch Points: If you hear gobbling from certain spots on ridges at first light, but then later only hear gobbling off the public parcel on nearby farms and other private lands, look over your map for pinch points where the turkeys are moving through from the roosts on public lands to the feeding areas on private property. Contour lines will often show just where they’ll descend and navigate between thick areas, ponds and other terrain. Set up with decoys and yelp and scratch the leaves. This tactic requires patience, but sooner or later a gobbler will come through.

Listen from the High Ground: Before the season, look over your maps for high points where you can get above a public area to listen at sunrise and sunset for gobbling in spots that are overlooked. I recently found the backside of a ridge in a popular area that drops into private land below. There, gobbling isn’t heard from the public area unless you climb the steep ridge far enough to hear the other side.

Henned-Up Toms: Depending on how warm and dry the spring is, hens will begin to leave their gobblers in mid-morning to lay an egg. Often this means that by mid-season dominant toms that have ignored calling find themselves lonely in late morning. These suddenly solitary gobblers can then be called in, and maps can reveal prime late-morning spots.