The Eastern population of greater sandhill cranes has grown about 4 percent annually since 1979 to an estimated 95,000 birds, but brace yourself for insults and acidic emails if you propose hunting them.

This particular crane population nests from eastern Minnesota and northern Iowa to southern Quebec and western New York. Their migration route to wintering grounds in Florida takes these 9- to 10-pound bugling birds through Indiana, Kentucky, Tennessee, northern Alabama and Georgia.

Much like most U.S. wildlife, sandhill cranes were nearly wiped out 100 years ago. Careful work by hunters and other conservationists helped restore their numbers, which wasn’t easy because of low reproductive rates and widespread wetland destruction. Still, the Eastern population keeps growing slowly and steadily.

Therefore, when a retired rural-sociology professor from the University of Wisconsin recently suggested a crane season for his state, he also extended an olive branch: Let’s direct all crane-hunting license revenues toward long-term research and management work for sandhills, including funds for private-sector conservation groups. Crane-hunting fees would provide more research for sandhills than the species has ever known, he predicted.

The response to professor Tom Heberlein’s idea was fast and mean. “What the (schmuck) are you thinking?” a man wrote. “You advocate shooting these majestic birds to make a few bucks to study them! Why don’t we have a hunting season on puppies and give the license money to the Humane Society?”

Another repeated old stereotypes: “Because it moves we should kill it? How do you justify this? Does it make you powerful and manly to shoot some creature who’s just trying to survive in an ever-decreasing wildlife environment?”

Yet another reader got goofy: “What’s next? How about robins, or something more sporty like hummingbirds?”

Well, now that you mention it, “Wehman’s Cook Book” from 1890 included a recipe specifying 10 or 12 stuffed robins, “previously rolled in flour” and seasoned with salt, pepper, parsley and eschalots. But let’s be fair: Heberlein never proposed hunting robins.

Realize, too, that greater sandhills have been hunted in Kentucky since 2011 and in Tennessee since 2013. Hunters in those states have bagged a combined 2,061 cranes since those inaugural seasons, an annual average of 344.

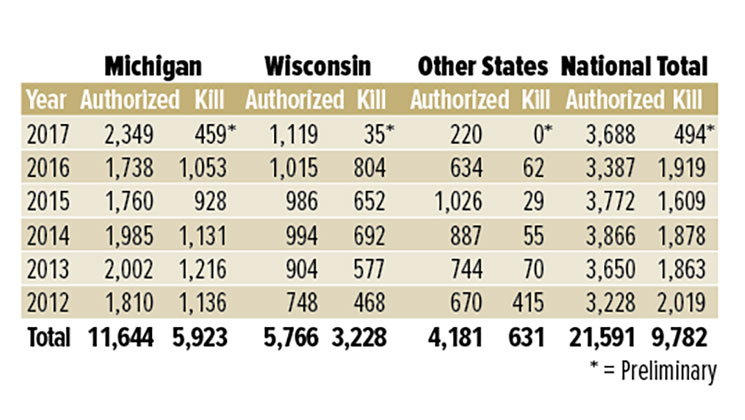

But that’s only about 15 percent of the human-caused deaths in the Eastern crane population. Would crane-hunt foes be kinder and gentler if they knew the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) authorized the killing of about 2,920 sandhill cranes annually in that population the past six years, which resulted in average annual kills of 1,525 since 2012?

The fact is, crop-damage complaints sparked most of the 9,782 crane-depredation shootings nationwide since 2012, with Michigan and Wisconsin accounting for 9,151 of them (93 percent). Neither state has a crane-hunting season, but each has lots of fertile fields near wetlands. Anne Lacey, a crane researcher with the International Crane Foundation, said all that prime food and habitat creates a “perfect confluence of corn and cranes” when corn seeds germinate in late spring.

Unfortunately, none of those nearly 10,000 beautiful, majestic, delicious sandhill cranes killed the past six years with crop-damage permits got plucked, skinned, smoked or cooked for table fare. Strict migratory-bird laws dictate that cranes killed with depredation permits cannot be eaten. They also can’t be preserved as taxidermy mounts for personal use. The carcasses are supposed to be burned or buried, but many likely rot where they fall and feed only scavengers.

Why such restrictions? Because federal agencies don’t want crop-damage programs to become pseudo hunting seasons. Here’s how the program works: When farmers see sandhill cranes sticking their long beaks into tilled fields to pluck freshly planted corn seeds in spring, or spearing and coring row after row of ripe potatoes in late summer, they ask the U.S. Department of Agriculture to help stop the destruction.

If deterrence fails, farmers can seek the death penalty by filing paperwork with the FWS for a shooting permit and kill quota. The state’s wildlife agency gets a heads-up, but because sandhills are international migratory birds, the FWS has jurisdiction. State wildlife agencies have little or no standing regarding the kills.

Unfortunately, none of those nearly 10,000 beautiful, majestic, delicious sandhill cranes killed the past six years with crop-damage permits got plucked, skinned, smoked or cooked for table fare.

Most crop-damage shooting permits get filled in spring, which concerns crane biologists. Sandhills don’t breed until their third or fourth spring, at which time they pair, get territorial and tend nests. Meanwhile, younger, unattached, nonbreeding sandhills move about in flocks to forage. Unless shooters study each situation carefully, they could shoot more breeding birds in spring than would ever get killed in a tightly regulated autumn hunting season.

The FWS would probably issue fewer crop-damage kill permits if more farmers planted seeds treated with liquid Avipel, which makes seeds taste awful. Once cranes realize the seeds aren’t edible, they often stay in the field but switch to insects, worms, mice and waste grains.

But Avipel isn’t free, which forces farmers to make tough cost-benefit business decisions. Avipel costs about $8 to $10 per acre of seed corn. Plus, farmers can’t always predict if or when cranes will ravage their crops each year. Therefore, a farmer could spend hundreds to thousands of dollars on unnecessary seed “insurance” on Avipel. And if a farmer treats more seeds than he plants, he’s stuck with it. Treated seeds aren’t guaranteed to repel cranes one year to the next.

It’s complicated stuff, these quests for cooperation and more hunting opportunities. But who can feel good about destroying thousands of sandhill cranes each year as if they’re a flying scourge or crop blight? Perhaps all that outrage against crane hunting should be directed elsewhere.

U.S. Sandhill Crane Depredation Kills

Since 2012, nearly 10,000 sandhill cranes have been killed nationwide under crop-damage permits issued by the federal government. Migratory-bird laws prohibit their consumption.