In the mid-1990s, seniors at Milton Area High School with plans of pursuing higher education, where they would come face to face with the dreaded college essay, took Mrs. Vickie Hort’s Advanced Composition class to prepare for the battles that lay ahead. Mrs. Hort regularly used words from the vocabulary list in casual conversation, and she urged her students to write even more precisely than she spoke. I distinctly recall one piece of instruction she delivered: Avoid using the words “very” and “really.” A writer should not pair either of these with an adjective or adverb, warned Mrs. Hort, because a better, more descriptive word likely exists to use in place of a modifier propped up by an intensifier.

Except in a scouting report presented on the eve of New Mexico’s opening day of elk rifle season.

“We saw some very nice bulls this morning,” said guide Miguel Rodriguez shortly after my hunting partners and I checked into the lodge at Express UU Bar Ranch, due south of Cimarron. “They bugled for a long time after daybreak. You guys hit it just right. Tomorrow should be really good.”

Granted, Miguel spoke those words; he was talking to a group of elk hunters, not composing a college paper. We graded him with excited smiles. But had he delivered his findings and prediction in written format, I don’t think even Mrs. Hort, if she were an elk hunter, would have found fault with them. “Very nice” and “really good” got the point across perfectly. It was plenty of emphasis to cause me to turn in early that night.

Twelve hours later I was searching for other words that would do the morning more justice. Like Miguel, I finally settled on “really good” because there was no sense trying to further describe the experience in a mere phrase. None of the adjectives in the English language were strong enough, and besides, we were still into elk.

It was midmorning, and bulls continued to bugle all around us. My guide, Dathion Gomez, and I had left his truck just as the rimrock above us started to turn from gray to pink. We’d seen elk immediately, but even before that we’d heard bulls bugle. From first light until 9 o’clock, multiple bulls sounded off several times every minute it seemed. One bull answered another only to be interrupted by a third and a fourth. And then the process would repeat, sometimes provoking a fifth and a sixth to scream out. We heard hundreds of bugles. For those who relish the sounds of an elk hunt as much as the sights (and who doesn’t?) it was a really good morning.

We followed the elk, which were divided into three loose herds, across the grass-covered lowland and into foothills scattered with junipers and head-high brush. Dathion and I used the terrain and its cover to close the distance, hoping to get within range of a particular bull we had been glassing for the past hour. The tall 6x6 had disappeared into a stand of junipers near the top of the hill we were climbing, and when a bull bugled just over the crest, we figured it was the one we were after.

We circled the hilltop, slipping through the shadows of the trees, until a cow and calf feeding in an opening less than 50 yards away blocked our approach. They were unaware of us as we tucked in closer to the branches of the nearest juniper. Dathion checked the breeze—perfect. Minutes later the pair drifted off through a patch of brush, and we crossed the end of the opening to continue our search for the bull.

We didn’t make it 20 yards when we heard crashing in the junipers and froze. A hollow, staccato popping sound came from the thick timber. I looked at my guide with a puzzled expression.

“That’s a bull tending a cow,” Dathion whispered, anticipating my question. “You only hear that when you’re really close to them.”

Though we were mostly exposed in the shin-high grass, we couldn’t risk retreating to cover. The bull was moving toward us, the popping getting louder. More crashing and then a cow emerged from the trees at a half-trot. She didn’t even glance in our direction as she cleared the opening and strode into the brush to our left.

I pointed my rifle toward the junipers and hoped the bull would stay focused on the fleeing cow. From the corner of my eye I caught movement, but it was up the hill and too far to the right to be the bull. Judging from the space that separated the tawny patches of hide I could see through the brush, two or three more elk were headed our way. I figured them for cows, as no antlers floated above the brush.

But then a bugle forced me to turn my head for a better view. A bull brought up the rear of this small group, and he was immediately challenged by the one popping off in the junipers. It was tough to tell which one was dominant, as each charged the other in an explosion of cracking branches and pounding hooves. They met in the trees with a smashing and grinding of antlers. The dispute was settled quickly when seconds later one thundered back up the hill.

Dathion and I strained to get a view of whichever bull remained. The fight had occurred just 30 or 40 yards away, but the low branches of the junipers hid the victor. We debated slipping ahead for a better look when another bull, this one downhill to our left, commanded us with a bugle to stay put. Evidently he was as interested in the fight as we were, because he wasted no time marching up the hill. His polished, yellow 6x6 rack glinted in the sun as he plowed his way through the brush. When the bull stepped into the opening, he was broadside at just 15 yards.

“Not the one we’re after,” Dathion said. “There are bigger bulls here.”

It seemed like that elk glared at us in disdain before he sauntered into the junipers. I shot a similar look at Dathion. Either my guide was crazy, really crazy, or the Express UU Bar was a special, very special, place to hunt elk.

■ ■ ■

Stretching across 180,000 acres of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains in northeastern New Mexico, the Express UU Bar Ranch was once part of one of the largest contiguous private landholdings in the United States. In 1841 the government of Mexico granted more than 1.7 million acres of frontier territory to French-Canadian trapper Carlos Beaubien and Mexican official Guadalupe Miranda to encourage settlement and cultivation. Eight years later Beaubien’s son-in-law, explorer Lucien B. Maxwell, took possession of the land and together with Kit Carson established the settlement of Rayado along the Santa Fe Trail.

Over the next 50 years the land included in the grant changed hands several times with portions sold to numerous individuals. In 1927 Oklahoma oilman Waite Phillips bought 300,000 acres, built his elaborate Villa Philmonte summer home on the land and later donated almost half of his holding to the Boy Scouts of America, which would establish Philmont Scout Ranch. Phillips, who enjoyed hunting, fishing and camping, retained the rest of the acreage for grazing cattle and named it the UU Bar Ranch.

Entrepreneur Bob Funk, founder and owner of the internationally successful staffing provider Express Employment Professionals, bought the UU Bar Ranch in 2006. Funk is a cowboy at heart, with a smile as wide as his 10-gallon hat, and made the UU Bar part of his Express Ranches operation to further the development of Angus and Hereford cattle seedstock. He also recognized the tremendous hunting opportunities the ranch offered and brought in a true elk expert to serve as general manager of Express UU Bar.

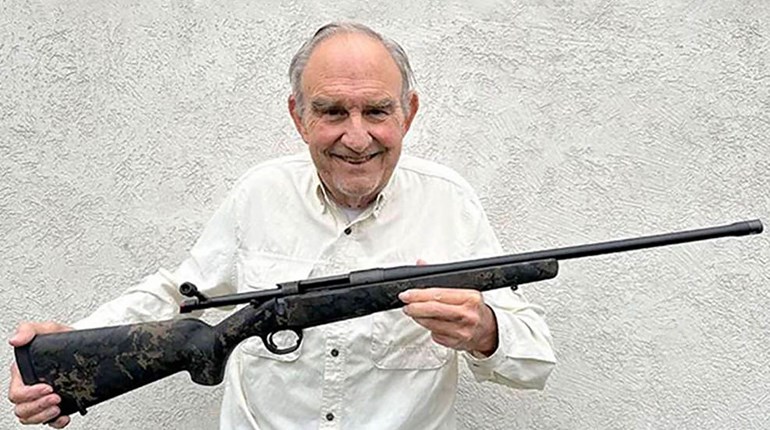

John Caid is a biologist who, during his 35 years with the White Mountain Apache Tribe Game and Fish Department in Arizona, was largely credited with elevating the trophy potential of the reservation’s elk herd. Before hiring on with Express UU Bar, Caid also served as chairman of the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation board and authored The Golden Age of Elk Hunting. The man knows elk and, as a guide, knows how to put hunters on them.

Caid’s experience in conservation, game management and habitat improvement steers the elk hunting program on the ranch, which emphasizes free-range trophy quality. Bulls in the 330- to 350-inch class are not uncommon. In recent years a few have even taped out above 370 inches.

■ ■ ■

Having learned all that at dinner after the first day’s hunt, I had no reason to question Dathion’s sanity the next morning. This was a high-end hunt, and he wanted me to make the most of it. Opportunities to hunt places like the Express UU Bar don’t come often, even in my job, and I wasn’t going to take it for granted. Nor would I fail to appreciate the commitment of a private landowner, a rancher, to boosting the quality of game on his property. This really was a very good place to hunt elk.

“Today we’re going to find a big bull,” said Dathion as daylight started to paint the sky over the wide mesa we were about to glass. “A really big bull.”

We had taken an ATV up a rocky ranch road, climbing above the foothills to top out on a rolling expanse of grassland ringed with pines. The plateau ran for miles—it was the largest on the ranch—and was about a mile wide. It didn’t take long to find elk grazing in the grass: a few cows and a bull that held my guide’s interest. The elk were more than 1,000 yards away and we had to get closer for a better look, but the cover gave out halfway. Crouching behind the low hill that hid our partial approach, Dathion and I took turns carefully raising our heads and binoculars above the crest to check out the bull as he circled his harem.

“That’s a bull we should kill,” Dathion said, “but we’re not going to get him from here. Let’s chill out and see what he does.”

Two hours later we were in the same spot. The bull had calmed down and bedded with the cows, which made it almost impossible to see him over the rise and through the grass. Since he wasn’t moving, we decided to go to him. We dropped below the crest of the hill and circled downwind. When we came over the top, well behind the elk, we realized the ground on that side rose to the herd as well. This was a more gradual slope, but it still blocked our view of the elk. All we could do was crawl a few yards and glass, crawl a few more yards and glass again.

Thirty minutes of belly time finally afforded us a clear look at the area where the elk had bedded—but they were gone. Whether we spooked them during the stalk or they simply moved out of the open to seek shade in the increasing heat, we’d never know. We stood and stretched and panned the plateau with our binos. The mirage from the ground quickly heating in the sun made it difficult to glass more than a half-mile.

“Let’s take a walk,” said Dathion. “Somewhere on this mesa are elk.”

Our course led us through the strip of timber along the edge of the plateau. We covered ground steadily, glassing across the top of the mesa as well as over its edge into the juniper thickets below. There wasn’t a single bugle to tip us off to a bull’s whereabouts. Compared to the symphony we had been treated to the morning before, the silence was deafening.

It was almost 11 o’clock before we saw another elk, a small bull feeding through an opening in the pines. We skirted him and glassed for more, but he was alone. The sun beat down on the mesa under a cloudless sky, and the temperature climbed. Dathion suggested we cross the plateau to poke around the darker timber on the other side. I felt the sunburn on my face and neck, realized I was getting low on water, and agreed some shade would be a good thing.

We never made it to the coolness of the trees. Halfway across the mesa we ran into elk, a large herd of cows with a few young bulls. They had been hidden by a fold in the terrain and a patch of junipers until our slight ascent revealed their presence. We watched them meander to the side of the mesa from which we had just come, and suddenly the strip of pines we had written off as deserted less than a half-hour ago was alive with bulls. Big bulls. They had been lying up in the scattered shade until the appearance of the cows spurred them to their feet. We’d abandoned our search about a quarter-mile too soon.

The bulls’ activity only increased as we stalked our way back to the tree line. A couple bugles soon grew into an uproar. The arrival of the ladies caused testosterone levels to skyrocket, and several fights broke out. By the time we reached the pines, it was outright pandemonium. Bulls dogged cows. Cows dodged bulls. Hooves thumped the ground and antlers raked the trees. There were bugles and grunts and mews and sounds I didn’t know elk could make.

We shadowed the elk for several hundred yards as they clamored through the timber. Though we were in range of bulls several times, we never got more than a glimpse of a rack before its carrier hustled off. When the herd left the pines for the open expanse of the mesa, we were looking at more than 100 elk.

“The one we want is in the middle,” said Dathion. “He’s a 7x7. We have to kill that bull!”

I agreed, but with dozens of cows surrounding him, I had no shot. The elk were 350 yards away, and there was nothing between us but grass. With no options for a stalk, all we could do was watch the action. The 7x7 was clearly the boss, and he circled the herd to chase off several satellite bulls. A few of them were brash enough to lock antlers with the monarch, but the scuffles didn’t last long.

Eventually the herd moved over the horizon, and Dathion and I followed just close enough to keep antlers in sight on the skyline. These maneuvers went on for more than an hour before it looked like we’d finally have a chance to close the distance. As the herd approached a draw between two small hills, we made a plan. One side of the draw was covered with juniper, and if we could make it to that without getting busted, I could perhaps sneak in for a clear shot.

Most of the cows had already moved into the draw when the big bull bringing up the rear did something we never imagined. He turned away from his herd and began walking in our direction, quartering toward us on the horizon. We couldn’t believe what was happening; this was a very lucky break. Dathion and I crouched in the grass and paralleled his path. When 200 yards separated us from the bull, I took a kneeling position behind my shooting sticks and prepared for a shot. He needed to come just 20 or 30 more yards to give me a clear angle to his vitals.

And then the bull bedded down.

The only parts of him visible above the grass were his ears and heavy, bladed antlers. I stayed on the sticks with the crosshair wobbling just over his neck. Ten minutes passed and I was still waiting. Then 20. Dathion bugled at him, hoping he would get up, but all the bull did was grunt back. My guide stood, even clapped his hands, but the bull remained in his bed.

We had resolved to keep calm and wait him out no matter how long it took when the bull’s rack began to tip—he was about to stand. As soon as he was on his feet, my .300 Win. Mag. cracked. When the first shot hit him, it was good. When the second connected, it was very good. And when the bull finally dropped to the ground at the third shot, with all due respect to Mrs. Hort, it was very, very good.