Ever notice how the best literature about hunting waterfowl is full of references to horrible weather?

The grand master of wingshooting, Nash Buckingham, wrote: “Booming thunder, jagged lightning and a high wind added nothing to that situation and by now, most of us realized that with 35 miles to voyage, we were facing an ‘out yonder’ capable of maturing into an extremely sloppy business.”

In Across the River and Into the Trees Hemingway wrote: “It was all ice, new-frozen during the sudden, windless cold of the night. It was rubbery and bending against the trust of the boatman’s oar. Then it would break as sharply as a pane of glass, but the boat made little forward progress.”

It’s the same with waterfowling art. Check out the best paintings at any Ducks Unlimited fundraiser; they will make you chilly just looking at them. The canvas will be filled with men with icicles in their beards, snow-covered dogs and sleet pounding the blinds.

All the great writers focused on the extreme weather associated with hunting waterfowl. I doubt any scribe ever wrote a treatise about the best sun block to use in a duck blind. In waterfowling art, you never see a guy in a tank top wearing sunglasses with zinc coating his nose. Everybody knows waterfowl hunting is at its best when the weather is at its worst.

If you are like me, your best days—the memories that stick—are the days that were nasty.

Like the day we tipped over the canoe in the middle of a sleet storm. We took turns diving off the riverbank into the cold water to find our shotguns while the temperature headed south with the setting sun. Our jackets froze, so we shed them and our shirts and we paddled hard, racing darkness through the remaining miles of river, bare-chested, to the truck. Only the exertion kept us warm. I can’t even tell you how many ducks we shot that day. It doesn’t matter anyway; they all floated away with the current while we were trying to survive.

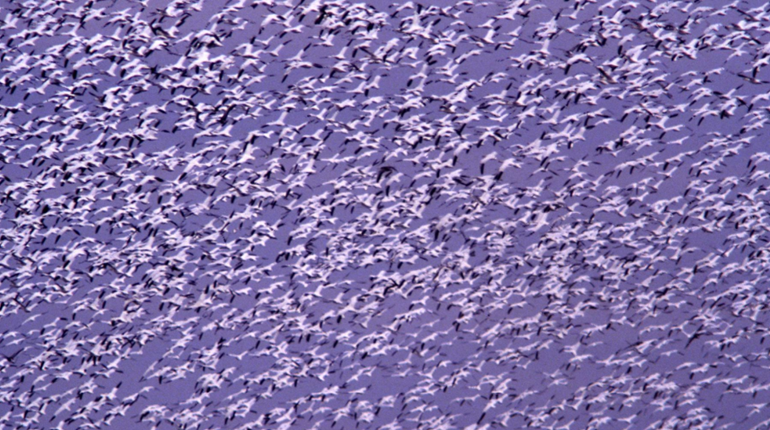

Or the morning we huddled in a rickety blind on the edge of Lake Champlain while a nor’easter raged. The snow was just a degree less than solid. The visibility was measured in feet. By the time the snow geese emerged from the storm they were over our heads and looked like ghosts misting though English fog. As they passed they seemed to develop slowly into substance, like an old black-and-white in a developing tray. I shot poorly that day and we lugged far too few geese back to the truck. I cared then. I do not now. As it turns out, there was more to the day than a body count.

I kept all that in mind while I was packing for an Alberta waterfowl extravaganza—three days of hunting multiple species of ducks and geese in the northlands. I just knew it would be cold. After all, the Canadian North Country wrote the book on nasty weather. In late September it can get pretty brutal out there on the windswept prairies. I packed wool and Gore-Tex, hand warmers and insulated boots. I packed layers to wear, from high-tech underwear to insulated parkas. I planned to hunt. I would never surrender to the legendary Canadian cold.

I think the coldest day we had dropped into the 80s. That’s good old American Fahrenheit degrees, none of that goofy metric stuff the Canadians use.

There was a bit of a chill in the mornings, the kind your grandmother would need a sweater for, but by mid-morning it was bikini weather. Thank God nobody wore one. The sun was bright, the sky was blue and the clouds were so high satellites flew under them. It was the exact opposite of the weather needed for good waterfowl hunting. It was the zig to good hunting’s zag, it was the yin to the yang, Mars vs. Venus. If PETA controlled the weather, this is what they would send to every waterfowl hunt.

To top it off, the lodge had some kind of water-heating plant under my bedroom that kept the temperature at least 10 degrees hotter than it was outside, even with the heat turned off. I am sure that’s a huge blessing on a normal hunting trip, but that thought eluded me as I tossed and turned, soaked in sweat.

I suppose any experienced hunter can see where this is headed. You must be thinking that we had a terrible hunt. We spent all that money, traveled thousands of miles only to be greeted with bitter disappointment—that we would have been lucky to have a single, sky-busting shot at a high-flying mallard.

But if you believe all that—and history says you should—you would be wrong.

We hammered them. Even though my wool shirts and Gore-Tex pants were a bit out of place, it was one of the best waterfowl hunts I have ever experienced. I am sure it’s the only one I came home from with peeling sunburn as well as a cooler full of ducks and geese.

The reason is simple: Rather than get “stuck on stupid” as so many hunters do and waste hours in unproductive blinds, we used an adaptive strategy that put a lot of birds in front of our shotguns.

I wish I could claim credit for the simple genius of the approach, but all the credit goes to Dan Frederick and his guides. The concept is so self-evident and so simple I am surprised I have not seen it implemented a lot more often in waterfowl camps. Sure, it’s a bit more work than just hunting the same old spots, but it produces results. I guess for a lot of guides and hunters, it’s just easier to stick with all the old spots and then blame the weather for poor hunting.

Even when it’s hot and sunny the birds, assuming they are in the area at all, have to eat, right? So each morning and each evening while we were hunting others scouted and located spots for our next hunt. Our spotter, Darryl Kublik, put some miles on his truck, driving and watching. If he spotted flocks of ducks or geese feeding in a field, particularly if they were in the same spot more than once, he made a note—not just whether there were birds in the field, but exactly where they were feeding.

I suppose waterfowl are like other critters, including humans: They have a comfort zone, a place they like, a place that is “their spot.” Food attracts birds. But in the farm belt of the Canadian prairies, food is everywhere. So why then do the ducks and geese show up in the same spot, day after day? Who knows?

Clearly there is something they like and they will fly over multiple fields with more food to get there. My guess is that it’s a social thing. They fly over a field, spot some other ducks or geese feeding and land to join their brethren. Nothing bad happens, so they decide it is a safe, well-lighted place. They go back a few more times, and keep going back until something changes.

Of course the “spots” are not permanent and will be used or abandoned based on factors like a dwindling food supply or hunting pressure. But for a period of time, if you find the spot, they will come.

How many times have you sat in an unproductive blind and watched flock after flock land in another location, often one that looks just like yours? Why do they do that? Who knows? But I know what you are thinking: “Why didn’t I put my blind over there?” Well, why didn’t you? Because it was already here, right? It was a lot of work to build this blind and it has produced well in the past, so it could heat up again.

Well, the guys at Ameri-Cana Expeditions don’t operate that way. They find the birds rather than hope the birds find them. They go to the spot where the birds are eating and build a blind—not just close to where they are feeding, but in the exact same place that they are eating. The guys have everything they need in a trailer—sections of fencing, camo cloth, wire ties, bushes and branches to weave in for cover and something to sit on. They pull up with the truck, build the blind, toss out a few decoys and then drive off, leaving hunters ready and waiting. Usually they do it all in about half an hour.

Being one of those guys who over-thinks things, I was sure the structure in the middle of an open field would spook the waterfowl, but I was wrong. The birds hardly paid any attention. It was just another patch of brush. Experienced birds get used to seeing coffin blinds and look for the shape, but this was just another blob of vegetation on the prairie.

Proper placement of the decoys and talented calling helps. It sends a message in duck dialect: “Ignore that leafy blob and come down here where you are welcome; we are friends and will keep you warm and safe.” Something like that. I really don’t know that much about duck psychology, but the ducks looked well-adjusted when they set their wings and dropped into the decoys.

When we were done hunting, the blind came down and everything went back in the trailer, even if we were returning to that spot that afternoon or the next morning. I guess the idea is to not give a duck or goose a lot of time to think about it. After all, it only takes one curious duck with a big mouth for word to get around.

Of course the biggest factor for success is timing. Going to a place where you saw birds last week is not going to be as productive as going to a place where they were feeding last night. The migration is on and there is a constant flow of birds passing through. They find food sources by watching the birds that came in ahead of them. But it’s a time of transition, a time of flux, so the spots are constantly changing. Fresh, up to date, real-time scouting is the key.

The secret to success, even when the weather is better suited for water skiing than goose hunting, is simple. Hunt where the birds were feeding a few hours ago, not a few days ago. Yesterday’s birds have moved south for the winter, so hunt today’s birds. Hang loose, stay flexible and ignore normal.

That’s what we did, and to steal a line from Robert Frost, “That has made all the difference.”