What is arguably the most famous hunt in American history became famous not because of what the hunter killed—but because of what he did not kill.

It was 1902. Theodore Roosevelt was hunting bear in the swamps of Mississippi. He was being guided by a gutsy Southerner who was an experienced bear hunter. The guide tracked down a bear and held it in place by a most daring technique—by lassoing it and then tying it to a tree. When Roosevelt arrived on the scene he felt sorry for the tethered bruin, and refused to shoot it.

This incident was immediately picked up by newspapers and publicized across the nation. (This was before radio or television, so people got their news from newspapers.) The public pretty soon was enamored of this story of a hapless bear being spared by Teddy Roosevelt. Young children became especially fond of this story. And it led to the creation of the toy known today as the Teddy bear.

Over the last 120-plus years, millions of parents, hunters or not, have purchased Teddy bears for their children. Nevertheless, today hardly anyone knows the real story behind the toy. In fact, the real story goes beyond Roosevelt, and involves a remarkable man named Holt Collier. Collier was an American hunter whose life defied incredible odds.

■ ■ ■

In fact, Holt Collier lived a life that defied history. Born a slave in Mississippi in 1846, he fought for the Confederacy during the Civil War. Yes, you did read it correctly—he was a slave who fought for the Confederacy. Slaves were forbidden from bearing anything that could become a weapon, let alone firearms, yet he bore arms and fought alongside white Southern soldiers. Even after the war, when thousands of former slaves migrated north for better opportunities, he proudly stayed back, preferring a livelihood by hunting, thus holding on to his Southern roots.

Collier’s family was owned by a well-connected pioneer Mississippi family named Hinds who owned large plantations. From about age 10, he spent his life mostly in or near Greenville, Miss. The Greenville plantation he lived on was surrounded mostly by a swampy wilderness with plenty of deer and bear.

His masters (a father-son duo who owned him) apparently saw a precocious sportsman in this slave child, for they took him hunting at an early age. They gave him a 12-gauge shotgun as his first gun (made by prestigious English gun company W & C Scott, which eventually became Webley & Scott). The young boy excelled at marksmanship, and his hunting enriched the masters’ dinner fare by bringing in ducks, geese and squirrels. Soon he advanced to killing deer and black bear. Indeed, he killed his first bear when he was just 10 years old. He would go on to bag more than 2,000 bears over his lifetime. He may very well be the most prolific bear hunter in American history.

In later life he would recall that as a young boy when he was shooting at birds, one of his masters told him he should keep firing with one shoulder until that shoulder got sore—then switch to the other shoulder. Thus he became an ambidextrous shooter who could shoot a long gun equally well from the left or the right shoulder. So good was his marksmanship that his owners would sometimes put him up in contests against the best white marksmen in the region, resulting in his owners collecting significant purses.

Thanks to this precocity in shooting skills, he received preferential treatment on the plantation, and thus he found himself excused from many of the menial tasks that befell other slave boys growing up on plantations.

Holt Collier was just 14 years old when his masters enlisted to fight for the Confederacy during the Civil War. He wanted to join them, but his masters objected. Collier was not dissuaded. After his masters had marched off, he decided he would join them come hell or high water. He waited for nightfall, and trudged through the swampy woods in the dark and reached the Mississippi River landing at Greenville where steamboats were being loaded with soldiers and supplies bound for Memphis, where his masters were also headed. He hid in one of the boats that night, the next day and the following night, and got to Memphis undetected—having had no food or water the whole time.

Officially he was a body servant to his masters as they began their military service, but no one could keep Collier away from armed action. In 1861, his masters were among the forces sent to Kentucky as part of the Confederate plan to prevent Kentucky from falling into Union hands. His entrée into armed action occurred in Kentucky during a skirmish where Collier, still in his early teens (and neither tall nor muscular), picked up a gun and began shooting at Union forces.

A skirmish where one white soldier mocked him and another defended him not only left an impression deep enough for him to recall decades later but also surely did make him feel proud to fight for the Confederacy. His bravado in that skirmish was just one of many instances where his actions made even the most bigoted men around him acknowledge he was no ordinary black slave.

The respect by white soldiers propelled him to the thick of action in 1862 at Shiloh, Tennessee, one of the most historic battles of the Civil War. The Confederate troops (40,000 strong) launched a surprise attack and were routing the Union troops (also about 40,000 men) when high-ranking Confederate Gen. Albert Sidney Johnston was killed. His replacement, Gen. P.G.T. Beauregard, ordered a retreat and planned to resume the battle the next day. That retreat enabled massive Union reinforcements to arrive into battle and defeat the Confederates. Even today, some historians believe Beauregard snatched defeat from the jaws of victory by this premature withdrawal. A decisive Confederate victory at Shiloh might very well have changed the outcome of the war.

In any case, Collier witnessed Johnston’s death and recalled it years later. “At the battle of Shiloh I was on the battlefield with Gen’l Albert Sidney Johnston. He was shot in the thigh and bled to death. We run smack over the Yankees and drove ’em into the river, took their encampment and captured everything. But after Gen’l Beauregard was put in command he laid over Sunday to fight Monday. Monday they had, I think, thirty thousand reinforcements on us, and tore the army all to pieces.” (Notice that he used the words “we” and “us” to refer to himself and his fellow Confederates—thus showing his unabashed identification as a Confederate soldier.)

While serving with the Mississippi forces, Collier became impressed by the brash attitude of the Ninth Texas Cavalry regiment that had come to Mississippi to fight for the Confederate cause. Thus, though still only 16 years old, he joined that Texas regiment, and served with them three years until the war’s end in 1865. He later said, “I was the only colored man in the whole entire regiment that was a sho’-nuff soldier. All my white friends was good to me. I was a boy, but I was a fine shot and a fine rider.”

■ ■ ■

Collier’s acute skills of observation, which had led his masters to turn him into a hunter even as a child, were even more useful during the war, where his roles included being a scout, spy and sharpshooter.

In one intriguing case during the Civil War, there was a white Mississippian who was betraying the South by stealing livestock and other supplies from local families and selling them at war prices to Union forces. This turncoat and several associates secluded themselves on a wooded island in the Mississippi River. Collier, still only a teenager, was sent in as a spy. He impersonated a runaway slave, and the unsuspecting men allowed him in to their camp. He carefully observed the island’s topography, the men’s activities, their weapons cache, etc., and left. One night several days later, Collier and four white companions quietly paddled a small boat to the island. Skulking through the woods, Collier guided them in the dark to the turncoats’ cabin. They could see it was lit inside by a lantern, indicating their subjects were inside. Thus they entered it, in a quiet but fearless commando style. Armed with quick-draw Colt revolvers, they subdued the surprised men inside the dimly lit cabin without firing a shot, and bound and gagged them. The next morning, a Union sutler’s boat came in to buy supplies, and the commandos disguised themselves as pro-Union men and walked on board. Within minutes, they captured the crew and boat, and used the boat to transport the turncoats and their loot back to the mainland. The turncoat leader was swiftly punished by execution.

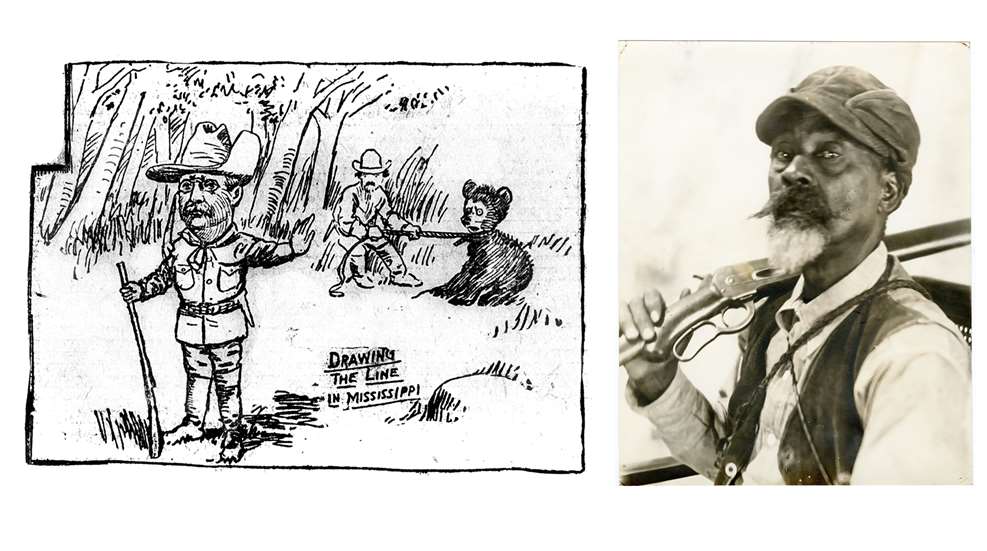

On another hunt Collier guided his friend Clive Metcalf. No that's not TR! In fact there are no photos of Collier and TR together.

On another hunt Collier guided his friend Clive Metcalf. No that's not TR! In fact there are no photos of Collier and TR together.

After the war, Collier went to Texas to see his friends from the Texas cavalry. There he quickly developed a reputation as a bronco-busting cowboy. After a year or so in Texas, he returned home to Mississippi.

So trusted was he by Mississippi authorities that, in 1881, he was asked to track down a white sheriff’s deputy who had turned against the law by killing two businessmen in Louisiana and fleeing the scene and crossing the river into Mississippi, thus becoming a fugitive. Collier tracked him down and, as the fugitive tried to shoot, Collier shot him first, killing him. This act of a black man shooting a white man, fugitive or not, would have meant instant death penalty for other black men—but not for Collier. He was acquitted on grounds of self-defense.

From the mid 1860s to 1870s, the South was under Reconstruction, the period when former Confederate states were re-admitted to the Union and the federal government in turn promoted massive rebuilding and infrastructure projects, which often involved timber-cutting and railroad-building, attracting thousands of workers. Collier realized he could make a decent living by supplying these industries with fresh meat via the one activity he had always relished: hunting. Thus began his career as a professional hunter. Deer and bear were his common quarries, and selling bear meat brought him a premium income. In the 1870s, an average bear could fetch him about $12. So, for instance, when he killed 75 bears in a season (which was not hard for him, as he killed more than 100 bears in some seasons), it meant an income of $900. That was more money than even many white Southerners earned in a whole year back then.

His typical method of hunting bear was with mixed-breed dogs. He would lead his pack of dogs who would tree a bear or corner it on the ground, whereupon he would shoot it or drive a knife into it. The latter method was particularly gutsy since it required the hunter to get right up to the bear (while the dogs kept it at bay) and stab it on the side opposite to where the hunter stood (so that as the bear turned its head toward the stabbed side, the hunter had a chance to get away), but many hunters including Collier never shied away from it. By 1890, he had killed more than 2,100 bears. By 1900, he was a regional legend.

■ ■ ■

Thus in 1902 when Roosevelt cottoned to the idea of a bear hunt in the Mississippi Delta, local organizers knew just the right man to guide him. They reached out to Collier—who was now 56 but still very much in the game—to plan the hunt and prepare a campsite. He chose a spot on the west bank of the Little Sunflower River, near what is now Onward, Miss.

While the hunt preparations were underway, Roosevelt got word that the powerbrokers who had invited him were envisioning a sort of communal hunt, where several hunters hunt together and a kill was considered a group achievement instead of an individual feat. Perturbed, Roosevelt immediately wrote a private letter to one of his hosts. What he wrote reveals a lot about his hunting philosophy—and it upends the belief held even today that when it comes to group hunting, the more the merrier. On the contrary, Roosevelt believed less is more. He wrote, “I am going on this hunt to kill a bear, not to see anyone else kill it. … As a rule, when I go hunting I do not like to take more than one friend with me, because when I hunt, I hunt. I don’t go for companionship—I go to get the game and I want to get it.”

The train that carried Roosevelt and his retinue—his staff, Secret Service agents, several businessmen and reporters—arrived in the Mississippi Delta near what is now Onward on the afternoon of Nov. 13, 1902. He was, after all, the sitting president of the United States, and there was no such thing as a private trip.

Collier was at the station. Roosevelt, extending his hand, introduced himself. Years later, Collier recalled Roosevelt as saying, “So dis is Holt, de guide. I hyar you’s er great bear hunter.” Collier’s characteristic Delta dialect is apparent in his version of Roosevelt’s greeting.

After loading the presidential luggage on a mule-drawn wagon, the hosts and the president rode horses to their campsite, which lay several miles away, deep in the Delta swamp, reached after traversing a forest of briars and thickets interspersed with tall stands of cypress trees.

That evening, Roosevelt told Collier he was counting on him to produce a bear. It would be a five-day hunt, but Roosevelt wanted to make a kill the first full day in the field. He also asked his hosts to skip the presidential honorifics and simply call him Colonel, a reference to his rank in the Spanish-American War just four years earlier. Thus, throughout the hunt Collier addressed Roosevelt as “Cunnel.”

"I am going on this hunt to kill a bear, not to see anyone else kill it. … As a rule, when I go hunting I do not like to take more than one friend with me, because when I hunt, I hunt. I don’t go for companionship—I go to get the game and I want to get it."

Before the hunt, Roosevelt got word the powerbrokers who had invited him envisioned a communal affair. A letter he wrote to one of them made clear his hunting philosophy.

Collier had decided the best way to meet Roosevelt’s insistence on getting a bear right away was to put him in a blind and try to drive the bear to him. Thus, on the first morning, he deposited Roosevelt and a friend in a blind near a watering hole frequented by a bear. This spot was about 2 miles from the campsite. He had scouted it before the hunt and knew it was a good spot. “I knew I could drive that bear right by him—same as anybody would drive a cow—an’ he’d get a shot ef he jes’ waited,” Collier recalled. “That was ’bout 8 o’clock in the morning. I told ’em to stay there ’til I got back.”

Collier then left Roosevelt and, getting on his horse, led his dogs through the swampy thickets and tangles. They got on the trail of the bear and followed it several miles, back and forth crossing the Little Sunflower River (a rather shallow stream fordable at many points when not swollen with rainwater). Roosevelt and his companion could hear the baying of the dogs, but the sounds became distant as the chase covered miles, and eventually the forest stopped transmitting the sounds. Bored by this silence, Roosevelt and his companion, in spite of the clear edict from Collier to stay put, decided they would break for lunch, and returned to camp.

What happened next at that spot epitomizes why a hunter—no matter how powerful he is—should always listen to his guide.

Collier described his pursuit of the bear: “I had been charging ’im and fightin’ ’im all day, runnin’ him ’bout in the open woods and tryin’ to make him go up a tree … and he would not take to a tree. I could have killed ’im a thousand times, but that would have spoiled the hunt … . It was terrible hot in the canebrake, an’ by me keepin’ between the bear an’ the river I knew he would sho’ly go to that waterin’ hole … .”

Surely enough, the bear headed to that watering hole—walking right by the blind where Roosevelt would have been sitting. But Roosevelt was back at the camp lunching—and thus lost what likely was an easy shot. Collier was not happy. “I sweated myself to death in that canebrake,” he griped. Now he had to deal with a bear that would have been shot by now but wasn’t. What’s more, he didn’t want to shoot it himself because he had promised Roosevelt the bear. The bear ran into the watering hole, with the dogs in pursuit. “The dogs were all fightin’ him pretty brash. But the Cunnel warn’t there. I didn’t want to kill the bear, but I jes’ couldn’t let him git away.”

Now the bear and the dogs were in the water in a fierce fight—and Collier jumped into the fray. “I had a little Scotch terrier named Jacko. He was fightin’ him from behind and watchin’ me. I had my rifle in my left hand an’ my lariat in my right hand. ‘Catch ’im, Jacko, catch ’im!’ Jacko jumped on his back from behind. The bear whirled roun’ and knocked Jacko into the water, and when he did I put my foot right between the bear’s legs, and when he raised his head out o’ the water I dropped the lariat over his neck and went out o’ the water and tied the other end to the willow tree. He caught another dog in there and I ran in to save the dog, and hit the bear with both hands across the head with my rifle. That knocked him down and broke his skull … I bent the breech of my rifle so I could not shoot it.”

In the meantime, a messenger had reached the lunching Roosevelt, who hurried back to the scene—to find a weary bear tethered to a tree. (Despite Collier’s blow, it had regained its feet and was alive, weary but alive.) Taken aback, Roosevelt put up his hand and said he couldn’t bring himself to shoot it. Collier recalled Roosevelt’s amazement at seeing the tethered bear. “The Cunnel looked at it a long time an’ asked how it was I did it, then he said, ‘That’s wonderful, wonderful—I never saw anything like that before.’” Since Roosevelt refused to shoot it, another hunter in the party dispatched the bear by stabbing it. The bear was a 235-pound male.

The above cartoon is a detail from a series called "The Passing Show" about President Theodore Roosevelt's purported refusal to shoot a chained bear while on a hunting trip in Mississippi.

The above cartoon is a detail from a series called "The Passing Show" about President Theodore Roosevelt's purported refusal to shoot a chained bear while on a hunting trip in Mississippi.

When Collier returned to camp that afternoon (Nov. 14, 1902) with the dead bear slung over his horse, a newspaper reporter asked if it was Roosevelt who had shot that bear. Collier replied that if Roosevelt “had stayed whar I put him, he would’er done got this yere one.” This comment was reported in major national newspapers, including The New York Times, which ran the story with a scolding sub-headline, “Mr. Roosevelt Might Have Shot the Game Had He Remained Where Old Hunter Placed Him.”

Roosevelt had ignored his guide’s advice by leaving his blind—but at least he redeemed himself by not shooting the tethered bruin. He did not realize that the fallout from this incident would make it the most remarkable hunting episode in American history.

A cartoonist at The Washington Post glommed on to the reports from Mississippi and created a cartoon where Roosevelt was shown with his upraised hand signaling his refusal to shoot the tethered bear that was endearingly portrayed as a distressed little cub (when in fact it was a mature bear). This cartoon, and its spin-offs, became a media sensation. In the public’s eye, Roosevelt the tough guy was now a man with a heart big enough to spare a little bear cub. Though Roosevelt had no luck on that five-day hunt and avoided even talking about that hunt, he had inadvertently endeared millions of people to him by refusing to shoot that bear. Capitalizing on the media sensation, in 1903 stores began selling stuffed toy bears called “Teddy’s Bears,” which later became Teddy bears—a toy for kids all over the world.

■ ■ ■

So, you see, the real story of the hunt that led to the most recognizable kids’ toy in the world involved a man that most hunters today have never even heard of. But it would be too simplistic to say Holt Collier’s only legacy is his role in that hunt with Roosevelt.

Collier’s life is a timeless example of what anyone can accomplish in America despite great odds. He was illiterate throughout his life—he could not even sign his name on his official Mississippi application for a Confederate pension and thus signed it with an X. Though he could neither read nor write, he apparently learned sufficient oral skills by listening to how his white contemporaries expressed themselves. His comments mentioned above were quotes various reporters wrote down while interviewing him.

Here was a man who was resented by many in his own race for fighting for the Confederacy, but he never strait-jacketed himself into a racial confine just because he was black. His supreme skills in pursuing wild game made him independent of anyone. In a way, he had emancipated himself by earning a living by hunting. And his skills were so respected that he was invited into the big leagues of hunting with the most powerful men of his time.

Much is made of Jackie Robinson breaking the color line in sports when he played Major League Baseball in 1947. But almost 50 years earlier, Collier had demonstrated in a major way that there was no color line in the sport of hunting in the first place, by hunting with none other than the president of the United States. After all, Robinson was neither born a slave nor raised a slave, but Collier was.

Indeed, Collier proved that hunting is the most egalitarian sport there is—a sport where your skin color is irrelevant to the outcome. After all, when you are in the woods, the animals don’t care whether you are black or white, their instinct is to evade you. Thus hunting inherently provides equal opportunity for people of all races, without needing government-enforced race-based programs, for there is no government program that can make a deer or bear stay still in front of your gun or bow just because you belong to a minority race.

In 2002, which marked the centennial of the famous hunt, Mississippi author Minor Ferris Buchanan published what is considered the most comprehensive biography of Collier, Holt Collier: His Life, His Roosevelt Hunts, and the Origin of the Teddy Bear. (It was an invaluable resource for me in researching Collier for this article.)

Buchanan writes, “Perhaps the most important legacy of Holt Collier is the character of Sam Fathers. William Faulkner’s Go Down, Moses, published in 1942, contains accounts of Sam Fathers that are inescapably analogous to the life of Holt Collier … . Prior to Collier’s death the Sam Fathers character was insignificant in Faulkner’s work. It is no accident that within six years of Collier’s death and the widespread re-telling of his life story, Faulkner significantly expanded and developed Sam Fathers’ character in five separate literary works. Faulkner, of course, was one of the most influential American writers of the 20th century and was from Mississippi.

Collier died in 1936, having lived 90 years. Today, his gravesite in Greenville has a long epitaph celebrating his life. Most notably, just 30 miles southeast of Greenville, several hundred acres of Delta woods have been set aside as the Holt Collier National Wildlife Refuge—the only federal wildlife refuge named after a black American. It is a fitting memorial to a man whose skills in pursuing wildlife enabled him to beat great odds in his own life.