“The credit belongs to the man … whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood; who strives valiantly … who comes short again and again … but who does actually strive to do the deeds; who knows great enthusiasms, the great devotions; who spends himself in a worthy cause … and who at the worst, if he fails, at least fails while daring greatly …”

—Theodore Roosevelt

I wiped a thin streak of blood spatter from my cheek with the back of my hand and winced at the gusto with which Harold applied his knife. The bloated innards from the wildebeest my hunting partner, JJ, shot the day before were now under the skinner/tracker’s rough blade, my hope of killing a leopard seasoning them like the grass seeds and dust whirling through the dry Namibia creek bottom. Ignoring the gore dripping from his dark fingers, Harold wrapped a cage of chicken wire around the 50-pound mass of paunch and intestines, binding it shut with a pair of rusty pliers. With cupped palms he ladled some of the wildebeest’s blood from a tub in the back of the Toyota, bathing the pale guts in bright crimson. He grunted at his helper, Johannes, and together the two began to drag the raw-smelling package toward a low-limbed camel thorn 200 yards down the sandy wash.

Nights later, a big male leopard skulked through the high grass and scrub downwind of the bait tree. The ripe odor from the torn paunch, combined with the stench of a slowly rotting zebra hindquarter hanging taut from one of the camel thorn’s bottom branches, caused him to pause. The smell of death was not unfamiliar to this killer—several of the rancher’s young cattle along with untold antelope and guinea fowl had made it quite common to him—yet the tang now filling his nostrils came from meat that was not his. With silent, practiced caution the leopard slipped into the creek bed, nearly invisible in the darkness but unknowingly deceiving his stealth with every step.

“This is a big cat,” said PH Jamy Traut when we found the leopard’s prints pocking the coarse sand the next morning. “His tracks are almost the size of the lioness. Let’s see if he ate.”

Nearly a week had passed since Harold and Johannes pulled the drag and hung the bait. Jamy’s trackers checked the area every day for sign but each time had nothing to report. JJ and I had stayed busy while we waited for a cat to come calling by keeping the camp supplied with meat. Springbok, blesbok, blue wildebeest and red hartebeest provided exciting stalks and excellent meals. Treading literally within spitting distance of a bright yellow Cape cobra one morning gave us a good snake story to tell our friends back home. We even took a roadtrip of several hundred kilometers to the Kalahari, where we killed two trophy gemsbok, caught springhare by hand at night and stayed up way too late around the campfire with a group of rowdy South Africans on a culling mission. It was all grand adventure and some of the best hunting of my life, but at times I could not help thinking of plains game as a mere warm-up, an opening act before the big show. Now that we had a leopard’s attention, I was ready to concentrate solely on the main attraction. My heart jumped at the thought of getting a chance at the big tom that very night.

This being my first try at leopard, I had much to learn. The first lesson came as we followed the cat’s tracks within feet of the bait tree, only to find with considerable disappointment the crafty carnivore had not so much as licked the zebra haunch. Seems as though we could lead a cat to bait—which the trackers accomplished with the drag—but we couldn’t make it eat. Jamy explained he, like most PHs, doesn’t like to sit over bait until a leopard has fed on it at least once. Twice is even better because it allows him to pattern the cat’s schedule and route to the bait tree then set up accordingly. Regardless of my enthusiasm for action, hunting this leopard was going to be a waiting game and would require a measure of patience beyond what I had employed over the past six days. Still, Jamy had a couple tricks to throw at ol’ Spots that we hoped would quickly tip the odds in our favor.

“He’s interested, but he’s not confident,” said the PH as he knelt to examine the tracks. “He’s a smart cat, maybe even has been shot at before. Now we need to tame him up a bit.”

Despite what anti-hunters and preservationists lead the public to believe, leopards are far from rare in central Namibia, Jamy noted. In fact, on places like the cattle ranch where we were hunting, they are populous enough to cause problems. (Earlier we had found tracks from three other leopards in the area.) Ranchers kill them in defense of their livestock, and there are still occasional reports of man-eaters. Judging by the size and location of the tracks in the creek bed, Jamy suspected this was the same leopard that killed five head of cattle on the ranch in the past year. He had a history with man, perhaps understanding he usually wasn’t welcome in our presence, and that wasn’t going to make him easy to invite to dinner.

There was another thing working against us. Leopards in the farm country of Namibia’s Central Plateau don’t have a difficult time keeping their bellies full. Along with clumsy cattle and sheep, the land teems with small antelope like steenbok and duiker, guinea fowl, and other assorted small, cowering creatures that make up a leopard’s preferred diet. This big cat simply may not have been hungry when he passed the bait, and besides, zebra wasn’t on his usual menu anyway. Experience had taught Jamy, however, that zebra was just the ticket to tempting a leopard’s taste buds.

“It’s the yellow fat,” he said, pointing to plates of the waxy stuff surrounding the muscles of the hindquarter. “Once a leopard gets a taste of it, he’ll be back. I’ve never had one feed on zebra and not return to the bait. We just need this one to take a bite.”

To give the cat one more reason to hit the bait, the PH instructed his pair of trackers to add water to the site. Leopards, according to Jamy, like to drink soon after feeding. Pieter and Johannes retrieved a plastic wash basin and a couple spades from the Land Cruiser and were soon digging a hole in the powdery ground beneath the camel thorn. When the hole was large enough to accommodate the basin, Pieter carefully set it in place, working dirt around the rim so the entire container was below ground level. Water to fill the basin came from several 2-liter soda bottles, some of which Pieter splashed randomly around the bait site to add the scent of damp earth to the air.

Meanwhile, Jamy and JJ secured a couple Bushnell game cameras to nearby trees. This technology seemed out of place with the idea of the classic leopard bait that had been formed in my mind by Ruark and Capstick, but it certainly gave us an advantage. Tracks only told so much. Now if the leopard visited the bait, we would know his exact size and feeding time. Jamy’s not the only PH in Africa putting game cameras to use for these reasons. In my mind I started to question whether all this human activity at the bait site—a fake waterhole, a spy cam—was counterproductive, but then I remembered Jamy telling me this leopard watered regularly at a cattle trough. Much like a whitetail, the cat was used to carefully coexisting with man and didn’t mind exploiting whatever improvements had been made to the landscape.

It seemed like the perfect setup. We gave the leopard an easy way to get a few days’ worth of supposed delectable meals, plus something to wash them down with. The tall grass and thick brush surrounding the creek bed—even the low-lying creek bed itself—gave him cover to ease his paranoia and perhaps a place to sleep off a belly full of meat. Jamy was sure it would work. I was sure it would work because Jamy was sure. Breeding confidence in the mind of his clients is one of the more delicate skills a good PH possesses, and I was already wondering if a leopard skin would fit above my couch.

“Let’s make a plan for a blind,” said the man who was going to contribute greatly to the interior decor of my home.

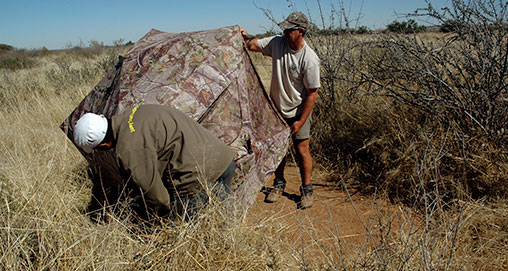

Again I was surprised at the modern approach to leopard baiting when Johannes returned from the truck with a pop-up blind stuffed under his arm. But it was just one part of the “plan”; the process that followed was bushcraft in the finest, most traditional sense, the end result a product of earnest labor and sweat under the late-morning sun.

Jamy selected a bush roughly twice the size of the two-man blind and 80 yards from the bait tree. After making sure there was a clear line of sight to the limb above the hindquarter—where the leopard, if feeding at dusk, would be silhouetted against the final rays of light—he pointed at the ground behind the bush. Johannes went to work with his panga, removing every twig and hint of vegetation until nothing remained in a 6-foot circle but silent sand. Setting the blind on this bed, Jamy climbed inside, opened the front window, and pointed out small branches and grass stems for the trackers to chop from the shooting lane. Joining Jamy and taking a seat on the shaded sand, I placed my rifle on the tripod he set up inside the window. Through the low-power scope I noted Pieter and Johannes had done their job well. In the 2 feet on either side of the Kimber’s muzzle, not a single obstruction remained to deflect a bullet on an unlucky course.

“How do you feel about that shot?” Jamy asked as I settled the little .308 into the cradle topping the tripod. “Make sure you can see under the bait and the branch above it.”

Placing the crosshairs of the Weaver just over the branch where the leopard would crouch to feed, I imagined centering them on one of the rosettes dotting his hide. Eighty yards from a rest with a gun that could hit a golf ball at 100 seemed like an easy shot. But when the time came, would I dare take it? I would probably get just one chance, and there would be more than one life riding on that single bullet. The relatively fragile leopard may be the easiest dangerous game to kill, but things could not get any messier if my shot resulted in a wounded cat. My primary job was quite bluntly to not screw it up.

I thought about the practice I had done in the months leading up to the safari. I had tried to make it as realistic as possible. Photos of leopards printed 75 percent of life size were the targets. I shot them at 50 yards while sitting and using a tripod as a rest. Practicing on an indoor range, I dimmed the lights until I could barely make out spots on the cats in the photos. I even had my colleague, Jon Draper, pose as the PH and tap me on the shoulder when he wanted me to shoot. Now was the time to have faith in my practice and my worth as a hunter.

“I’m solid,” I said after I braced the rifle as much as my mind. “If that cat comes to the tree, I can shoot him.”

While Jamy and I made sure everything was in order inside the blind, the trackers were busy with its exterior. They cut armfuls of brush and gathered heaps of dead grass, loosely weaving them together to disguise the blind’s outline. What looked like a random selection of vegetation was actually carefully planned. They never cut an entire bush or completely cleared an area of grass, instead leaving plenty of stuff standing around the blind to make it seem as if the area was undisturbed. When they were finished, the structure was virtually invisible, blending so well with the landscape it seemed as though it wasn’t there.

Satisfied with the setup, Jamy directed us to the Cruiser. “Tomorrow morning,” he said as we drove out of the creek bottom, “we will know if we are going to kill this leopard.”

We all expected to find a ravaged hindquarter or at least fresh tracks when we checked the bait after a night of anticipation, but expectations sometimes do not bear out in reality. The sand had no new story to tell, the zebra hung intact. The cat that had walked within an easy leap of our bait tree never returned during the rest of my safari.

We looked for—and found—sign from other leopards in the rocky Great Escarpment region to the north, but these cats gave us even less information to use against them. It was obvious my best chance was with the leopard in the creek bottom. At least I had that chance. In order to lose against a leopard, I had to hunt one. That’s failure I can accept.