Recently, I had my .280 Ackley rebarreled with a 26” stainless blank from Lilja. It was a great all-around rifle with the 24” Douglas barrel that it wore for 10+ years, but now I have a larger selection of big game rifles to choose from and I wanted something that filled a more specific niche. This rifle is to be used to send 140 gr. bullets as fast as I can push them while maintaining accuracy, for hunting deer in wide-open spaces. Essentially, I’ve always wondered what the rifle would do with a 26” barrel and it was time to find out. Practical? No. It’s my money (no, I don’t get free barrels).

The Background

The process of breaking-in a new barrel is designed to remove any burrs, imperfections, or other abnormalities caused by the chambering process. Premium barrels such as this Lilja are hand-lapped and inspected by the manufacturer so they are free from imperfections when they leave their shop. The problem is that your gunmaker is going to take a chambering reamer covered in lube and force it into that pristine barrel in the lathe. When steel is spinning, the reamer is cutting, and metal chips are flowing, things can get scratched or gouged. Breaking-in the barrel is designed to remove those imperfections via high velocity bullets. The bullet burnishes the hard edges as it impacts them, and constantly cleaning the bore means the bullet it hitting raw steel, not copper fouling

The Process

Every barrel maker has their own recommendation for break-in but they’re all similar: the barrel is shot and then cleaned at various increasing intervals. This is my method:

• Clean the bore when it arrives, the rifle has likely been test-fired, so it has some fouling already. Always use a bore guide and a high-quality one-piece rod such as a coated Dewey. You’ll also need a good copper solvent (Lilja recommends Butch’s Bore Shine), a bronze or nylon brush (never steel) and a pile of patches.

• Fire one shot and follow the solvent’s instructions until the barrel is totally free of copper, this will take forever and will likely cause you to use foul language (especially if your bronze brush falls into the sand and you have to revert to using only patches—ask me how I know).

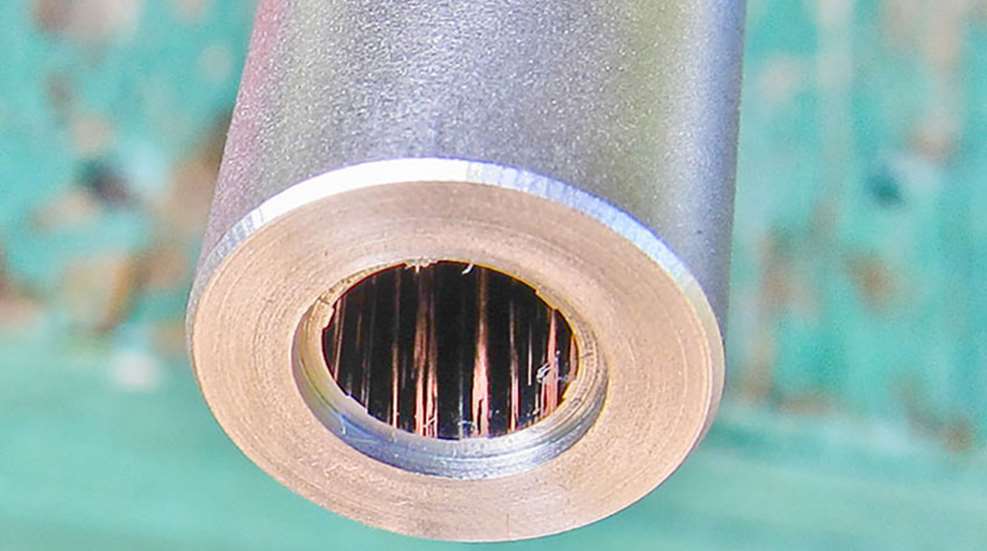

You can literally see the copper fouling in this barrel.

You can literally see the copper fouling in this barrel.

• Fire another round and clean, repeat for 10-12 rounds.

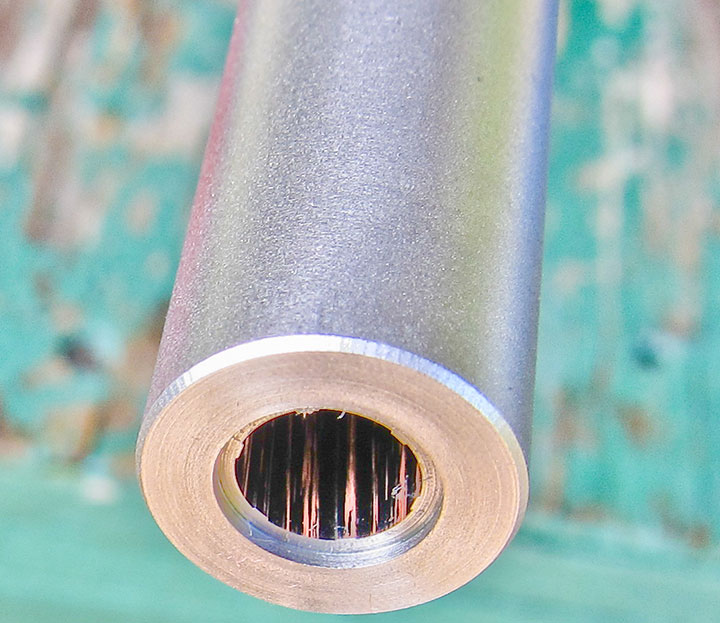

This barrel is still showing indications of copper, better keep scrubbing.

• Fire three rounds and clean, the barrel should be getting easier to clean.

• Repeat for 5 or so groups and then clean every 10 to 12 rounds until you get about 50 to 60 rounds.

Breaking-in a new barrel is a time-consuming process.

Breaking-in a new barrel is a time-consuming process.

By now, the barrel should clean pretty easily and you’ll have bunch of fired brass to handload with. I use mild loads (book minimums) for break-in for a variety of reasons: light recoil, less heat, and less barrel erosion. I also use whatever the cheapest jacketed bullets are that I have for that caliber, but I don’t recommend monolithic bullets for break-in.

Is it worth it? Every premium barrel maker that I have ever purchased a barrel from (Kreiger, Lilja, etc.) has recommended breaking-in their barrels. That said, a few days after I finished this process, I ran into custom rifle builder Charlie Sisk at J. Guthrie’s memorial service. I asked him what he thought of the process and his reply was essentially that it’s a waste of time and ammo.

“I shoot a custom barrel until the fouling causes the accuracy to deteriorate and then I clean it," he said. "A properly-chambered barrel won’t have any problems and the barrel itself has already been lapped.”

Charlie builds some very accurate rifles and knows far more than I do on the subject so I wasn’t about to argue with him. Candidly, it’s hard to prove an outcome in a quantifiable way without testing a whole pile of identical barrels. This isn’t going to happen so I follow the instructions of the guys who have produced tens of thousands of barrels with their names stamped on them. For me, it’s worth it since it allows me to get to know the rifle, get the scope more-or-less zeroed, and produce a bunch of brass that I can neck-size. Besides, how often do you get a new custom barrel?

My Conclusion

As long as you do it correctly, it can’t hurt and could give you an accuracy edge. You can’t go wrong taking the advice of barrel makers and benchrest shooters. Then again, does it make any difference you’d notice on a big game rifle? I seriously doubt it. It’s still a free country, you decide.